Read the full story here: The Northwood Murderer.

Saturday, December 30, 2023

Georgianna Lovering.

Saturday, December 23, 2023

Shot on Christmas Eve.

- The Boston Herald’s vivid description of the murder of Josephine Brown on Christmas Eve, 1891.

Read the full story here: Two Shots, A Shriek.

Saturday, December 16, 2023

The Home of the Benders.

Saturday, December 9, 2023

Mad with Jealousy.

Saturday, December 2, 2023

Tom and Catherine.

The morning of February 5, 1895, Dr. John E Rader was found murdered in the house of Mrs. Catherine McQuinn in Jackson, Kentucky. Catherine told police they were drinking whiskey with her paramour Tom Smith and when Tom passed out, Dr. Rader assaulted her. She shot him in self-defense.

Catherine could have committed the murder; she was a rough, course woman with a bad reputation. But the police were inclined to suspect her lover, “Bad Tom” Smith. He had been indicted for murder seven times before but escaped justice when crucial witnesses disappeared. This time, however, his luck ran out. Both Tom and Catherine were convicted of first-degree murder.

Saturday, November 25, 2023

A Fatal Frolic.

Sources:

“Fate of a Practical Joker,” Aberdeen Weekly News, February 20, 1891.

“State News,” Blount County News-Dispatch, January 1, 1891.

Saturday, November 18, 2023

A Fan's Obsession.

Read the full story here: Lunatic Dougherty.

Saturday, November 11, 2023

Love and Lunacy.

Saturday, November 4, 2023

Special Guests.

|

Elizabeth Kerri Mahon - May 7, 2011 Author and blogger, Elizabeth Kerri Mahon, shared the story

of Mary Ellen Plesant, one of several dozen brazen ladies— famous and

infamous—profiled in her fascinating book Scandalous Women: The Lives and

Loves of History's Most Notorious Women. |

|

Cheri Farnsworth - July 16, 2011 Cheri Farnsworth writes about murder and hauntings in Northern New York State. She shared this story from her book Murder and Mayhem in Jefferson County. The “Watertown Trunk Murder” – Hounsfield, 1908’ |

|

"Headsman" - Executed Today Since 2011, Headsman, the enigmatic blogger at ExecutedToday.com has shared execution tales of five 19th Century American murders: 1858: Marion Ira Stout, for loving his sister - 9/10/2011 1887: William Jackson Marion, who’d be pardoned 100 years later - 5/11/2013 1897: Ernest and Alexis Blanc, brothers in blood - 4/12/2014 1846: Elizabeth Van Valkenburgh, in her rocking chair - 11/1/2014 Six Men Hanged - 2/25/2020 |

|

Anthony Vaver - October 8, 2011

Anthony Vaver is an author and blogger (Early American Crime) who writes about crime, criminals, and punishments from America's past. This story is from his book Bound with an Iron Chain: The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America. Charles O’Donnel: His Life and Confession |

|

James Schmidt - March 9, 2013

James Schmidt has written several books about the American Civil War, including Galveston and the Civil War: An Island City in the Maelstrom. This story is a break from the battlefield, but not from violence - a fascinating tale of murder in Connecticut from the 1850s. "Murdered by a Maniac" Guest Post by James Schmidt |

|

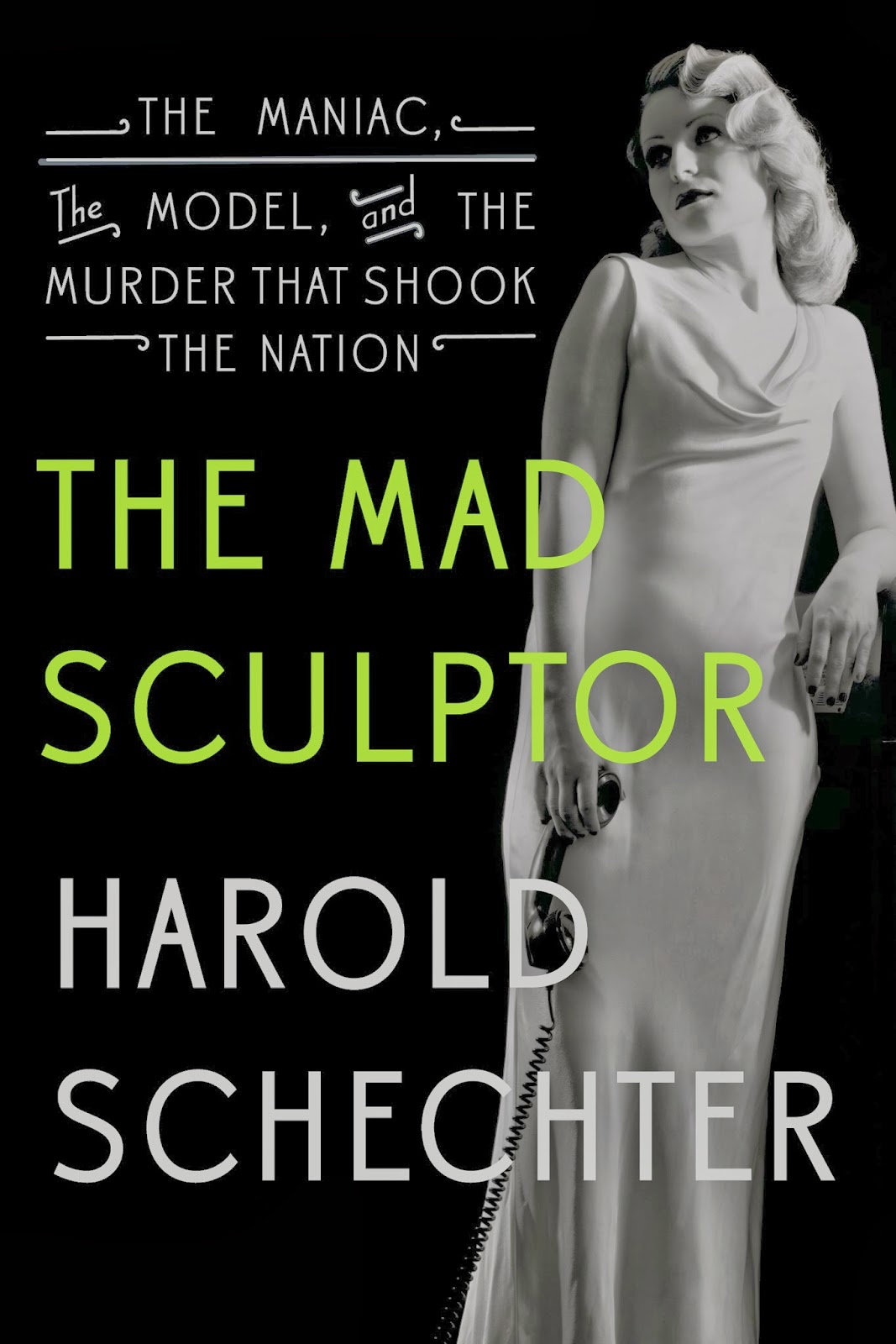

Harold Schechter - February 19, 2014

Harold Schecter, the master of historical true crime, included Murder by Gaslight in his blog tour promoting the book The Mad Sculptor. He gave a synopsis of the book and described his writing process. The Mad Sculptor: The Maniac, The Model, and the Murder that Shook The Nation |

|

Kyle Dalton - November 11, 2019

Historian Kyle Dalton works at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine and maintains the website British Tars: 1740-1790. He shared the story of the assassination of Captain Watkins Assassination of Captain Watkins |

|

Undine - December 16, 2019 Undine, "Blogger of the Grotesque and Arabesque. Remarkably lifelike," plies her trade at Strange Company. She related the murder of Olive Peany, an ambitious but hard to please Ohio girl. |

|

Shelley Dziedzic - January 18, 2020

Shelley Dziedzic blogs at Lizzie Borden Warps & Wefts, the prime source for accurate information on the Borden murders. Her post tells the story of a gruesome murder/suicide from another branch of the Borden family tree. Murder in the Well |

|

Don Everett Smith Jr. - March 14, 2020

Don Everett Smith revisited the 1850 Van Winkle killings, expanding on his book, The Goffle Road Murders of Passaic County. Revisiting the Goffle Road Murders |

|

Howard and Nina Brown Howard and Nina Brown run JTRForums.com, a discussion group for all things related to Jack the Ripper. They provided two posts on Ameer Ben Ali, arrested for the murder of Carrie Brown, considered by some to be an American victim of Jack the Ripper. Ameer Ben Ali & an Actor's Tale.- October 17, 2020 The Rescue of Ameer Ben Ali.- February 6, 2021 |

|

Donna Wells - April 16, 2022

Donna Wells, a former archivist with the Boston Police Department, shared an old photograph she found, believed to be a portrait of Jesse Pomeroy, who, at age 14, who murdered two children in Boston. Rare Photo of America's Youngest Serial Killer. |

|

Bob Moody - May 6, 2022

Bob Moody, a retired radio personality, chronicled the murder of his great-great-granduncle, Tom Moody, in his book, The Terror of Indiana; Bent Jones & The Moody-Tolliver Feud. His post relates the events leading to the feud and the murder. The Moody-Tolliver Feud. |

Sunday, October 29, 2023

Jacob S. Harden.

Saturday, October 21, 2023

Rum and the Knife.

Saturday, October 14, 2023

The Remains of Schilling.

In 1874, a feud within Cincinnati’s German community led to the brutal murder and illegal cremation of Herman Schilling. The case would also serve as a stepping stone for Lafcadio Hearn, a young aspiring journalist and illustrator on his way to international literary renown.

Read the full story here: The Tanyard Murder.

Saturday, October 7, 2023

A Fiend and a Shotgun.

Read the full story here: The Rockville Tragedy.

Saturday, September 30, 2023

A Murdered Mother.

His last words were, “I will answer to God for what I have done and forgive all.”

Sources:

“Convicted of the Murder of his Mother,” Evening Post, May 2, 1889.

“Elmer Sharkey Convicted,” Democratic Northwest., May 16, 1889.

“Found Murdered in Her Bed,” Cleveland Leader AND MORNING HERALD., January 13, 1889.

“Got a NEw Trial,” Lexington Herald Leader, November 20, 1889.

“Her Skull was Crushed,” National Police Gazette, February 2, 1889.

“Killed By Her Son,” Plain Dealer, January 15, 1889.

“A Murdered Mother,” Evening Post., January 14, 1889.

“Murderer Sharkey to Hang,” Ccourier-Post, May 22, 1889.

“News Article,” Erie Morning Dispatch, April 1, 1890.

“News Of The State,” Plain Dealer, February 26, 1890.

“Respited,” The Dayton Herald, November 20, 1889.

“Sharkey Must Go,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, July 25, 1890.

“A Stay of Execution Granted ,” The Piqua Daily Call, August 3, 1889.

“Two Murderers Hang,” The Daily Interocean, December 19, 1890.

“A Young Fiend,” Cleveland Leader AND MORNING HERALD., January 15, 1889.

Saturday, September 23, 2023

Political Protection.

William Farrell, Patrick Muldoon, and “Tonce” Joy played cards in Muldoon’s Cincinnati saloon on November 30, 1896. They were secretly colluding to cheat a fourth man. After skinning their victim, Joy’s job was to steer him away, but when he returned for his share, his partners wouldn’t pay. A fight ensued, a pistol fired, and “Tonce” Joy stagged out of Muldoon’s saloon to die. Farrell and Muldoon were politically connected, and after their arrests, a policeman named James Welton came forward with another story. He claimed that Joy, drunk and abusive, grabbed his revolver during a scuffle, and it accidentally fired. Regardless of which account was true, the DA did not have enough evidence to prosecute anyone.

Saturday, September 16, 2023

Saturday, September 9, 2023

Harry and Elizabeth.

In 1888, Harry moved to Omaha, promising to send Elizabeth money and bring her along when he was settled in business. The money stopped coming, so Elizabeth followed him to Omaha, only to learn he had married another woman. She and Henry spoke briefly in the parlor of the Paxton Hotel, then, as he turned to walk away, Elizabeth shot him four times in the back. Public sympathy was on Elizabeth’s side, and when the case went to trial, the jury deliberated for only thirty-five minutes before finding her not guilty.

Saturday, September 2, 2023

The Groton Tragedy.

Joseph Crue returned from work to his farm in Groton, near Ayer, Massachusetts, about 8:00 on the evening ofvening of January 18, 1880. He was surprised to find all the doors locked and curtains closed. His wife, Maria, should have been inside, but there was no response when he knocked on the door. He found the hatchway to the cellar partly opened, so he entered that way. He lit a lamp in the kitchen and searched the dark house for his wife. He found her lying dead in the bedroom, shot three times in the face and once in the chest.

Saturday, August 26, 2023

Morbid and Melancholy.

|

| Cora Marston. |

Read the full story here: The Dedham Tragedy.

Saturday, August 19, 2023

A Courtroom Melee.

|

|

In November 1889, Henry Miller, of Brownsburg,

Virginia, went to the home of Dr. Zachariah Walker to pick up a prescription. The

doctor was not available, so his wife Bettie prepared the medicine. While

alone with Bettie Walker, Miller could not control himself. He tried to kiss her, “offering

other indignities which were repulsed." When Dr Walker learned of this he

grabbed his shotgun intending to kill Henry Miller on sight. But before Walker

could act Miller brought charges against him.

Both families were prominent and well respected but on the

day of the hearing neither showed any sign of civility. As tensions mounted,

the full courtroom erupted into a general melee. Guns and knives were drawn and

by the end of the battle Zachariah Walker, Bettie Walker and Henry Miller were

all dead, and three others were seriously wounded.

Read the full story here: Disorder in Court.

Saturday, August 12, 2023

Bartholomew Burke's Murder.

Saturday, August 5, 2023

A Youthful Patricide.

Yesterday had been strange; Frank told the family he would be gone for ten days but returned the same night. He handed his wife a letter he had written to her. It was tender and remorseful, promising that Frank would change his ways. The bickering and quarreling between his parents had gone on throughout Herbert’s life. The fights were loud and very public; the family moved several times to protect their reputation before settling in Elmira, New York. Mrs. Warren thanked Frank for his new-found kindness and promised to do whatever she could to make their household happy.

They talked for hours, but by 2:00, they were fighting again. Their problems stemmed from Frank’s philandering, and he could not fix them that easily. Mrs. Warren knew that Frank stayed with other women during his long absences. She found love letters sent to Frank by other women, and when she confronted him, he turned violent.

Saturday, July 29, 2023

Anna Wheeler's Killer.

Read the full story here: Insane Jealousy

Saturday, July 22, 2023

"With My Knife I Cut Her Throat."

Jesse Pomeroy was 14 years old in 1874 when he stabbed and killed 10-year-old Katie Curran in South Boston. Less than a month later he stabbed and mutilated 4-year-old Horace Millen. Prior to the murders, Jesse had been sentenced to the reformatory for torturing and sexually abusing several other children but was released on probation. After conviction for murder, Jesse Pomeroy would spend his next 53 years in prison.

Read the full story here: Jesse Pomeroy - "Boston Boy Fiend."

Saturday, July 15, 2023

A Rejected Suitor.

Erving’s only flaw was that he was quick to anger and would act out of passion. This was a problem when Erving became infatuated with Dr. Johnson’s daughter, Jane, a highly educated and refined young lady. He repeatedly asked her to marry him and each time she told him, in no uncertain terms, that she was not interested. The family, too, discouraged any notion of a courtship between Erving and Jane. Each rejection increased Erving’s anger.

Saturday, July 8, 2023

A Murderer Murdered.

Read the full story here: The Walton-Matthews Tragedy.

Saturday, July 1, 2023

The Schoonmaker Tragedy.

“No more happy and loving couple could be found,” said Harry’s father, Col. John B. Schoonmaker, “So far as I knew, they never had a quarrel, and all was love and happiness.”

But in December 1888, Harry began acting strangely. His parents noticed he was irritable, and his talk was flighty. Others said he was “…alternately excited and depressed as if he was addicted to the use of opium or some other drug.”

Saturday, June 24, 2023

A Mafia Murder?

In 1896, Salvatore Serrio was killed in a shootout at the Brooklyn saloon of Joseph Catanazaro. The police arrested several Italian men allegedly involved in the melee. Throughout the summer, the police and newspapers referred to the case as a Mafia vendetta. Saloonkeeper Catanazaro and other prominent members of Brooklyn’s Italian community vehemently denied the existence of any such organization as the Mafia.

Read the full story here: Italian Vendetta.

Saturday, June 17, 2023

A Convenient Murder.

|

|

|

Amos J. Stillwell, a wealthy and prominent businessman in

Hannibal, Missouri, was 65 years old in 1889. His wife, Fannie, was 30 years younger.

On December 29, 1889, someone crept into their bedroom and murdered Amos with

an axe while Fannie lay sleeping in a separate bed with their children.

Dr. Joseph C. Hearne, who lived nearby, had been treating Fannie since before the murder. He and Fannie were married the following December. After

a long investigation, the police arrested both for Amos’s murder. Neither was

convicted.

Read the full story here: The Stillwell Murder.

Saturday, June 10, 2023

The Murder of Uri Carruth.

Charles Landis and Uri Carruth had been feuding for years. Landis founded the town of Vineland in 1861. It was a teetotaling community built on 50,000 acres of New Jersey wilderness which Landis owned. Carruth, the publisher of the Vineland Independent, was critical of Vineland’s policies and printed articles to humiliate Landis. In 1875, Carruth went too far when a story he published offended Landis’s pregnant wife. Charles Landis went to Carruth’s office with a revolver and shot the publisher. Though it took Carruth four months to die, Landis was charged with his murder.

Read the full story here: Tragedy at Vineland.

Saturday, June 3, 2023

Escape from the Death-House.

At the south end of the corridor was a lean-to building called the death-cell, which housed the electric chair. Sing Sing installed the electric chair in 1891, and on July 7 of that year, four condemned murderers were electrocuted. The chair sat idle for nearly two years, but in April 1893, the death-house had five inmates awaiting execution— Carlyle W. Harris, John L. Osmond, Michael Geoghegan, Frank Rohle, and Thomas Pallister.

.jpg)