Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Scott Jackson.

Saturday, December 25, 2021

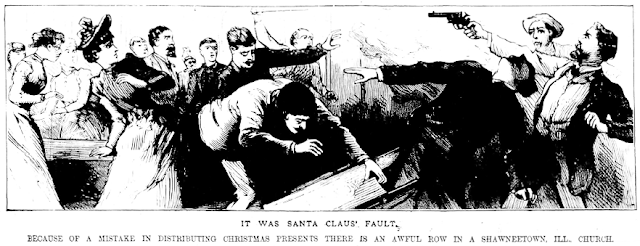

It was Santa Claus' Fault.

Sources:

“A Free Fight in a Church,” Boston Herald, December 26, 1889.

“It Was Santa Claus' Fault,” National Police Gazette, January 11, 1890.

“Wound Up om a Free Fight,” New York Herald, December 26, 1889.

Monday, December 20, 2021

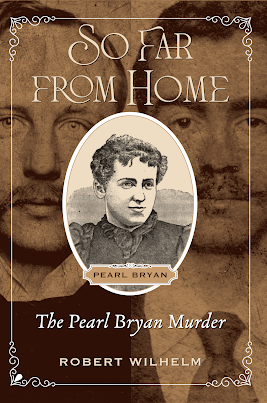

So Far from Home.

New Book!

The Pearl Bryan Murder

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Murder of Col. Sharp.

Saturday, December 11, 2021

Michael M’Garvey.

The evening of November 21, 1828, Michael M’Garvey violently chastised his wife, Margaret, in the room, they occupied on the top floor of a house at the corner of Pine and Ball Alleys, between Third and Fourth Streets, and between South and Shippen Streets in Philadelphia. He tied her by the hair to a bedpost and began beating her, unmercifully with a whip, continuing at intervals for the next hour and a half. When she passed out, he attempted to throw her out the window but pulled her back in when someone outside saw him and cried out.

Saturday, December 4, 2021

The Wife's Lament.

The business was doing well, and the two men got along until O’Keefe moved in. That winter they frequently argued over the way Kenney was treating O’Keefe’s sister. Kenney was a quiet man when sober, but aggressive when drunk, which became increasingly frequent. The arguments sometimes turned violent with punches thrown and bottles broken. Kenney ordered O’Keefe out of the house. O’Keefe refused to leave, and his sister took his side. O’Keefe remained but the two men barely spoke to each other.

At dinner on May 2, 1872, O’Keefe asked Kenney about the store. Kenney had been drinking heavily for several days and O’Keefe worried that it would hurt their sales. Kenney told him to mind his own business, but since the store was O’Keefe’s business, the argument escalated. When the subject of Kenney’s cruel treatment of his wife arose again, Kenney jump up and said, “Come down to the green and we will settle this matter.” Mrs. Kenney interceded then and separated them.

Around 8:00 that night, as Kenney was waiting on a customer and O’Keefe came to the barroom door and looked in. When Kenney was through with the customer, he went outside, and the argument started up again on the sidewalk. A scuffle ensued, they clinched and fell to the ground. O’Keefe pulled a jackknife from his pocket and stabbed Kenney in the neck. Kenney exclaimed, “I am killed.” O’Keefe took off down the alley.

Kenney managed to raise himself from the sidewalk and staggered into the store with blood streaming from his neck. Medical aid was summoned, but O’Keefe had severed Kenney’s jugular vein and he died before the doctors arrived. His wife bent over him, frantically imploring him to speak to her. “Who did this?” she asked, “What did Peter do that they should kill him.” She continued to lament over her husband’s body until someone removed her to a neighboring house.

O’Keefe entered the house through the backdoor, ran upstairs, and changed his clothes. He went back out through the barroom door where officers Dudley and Johnson were waiting for him. At the police station, O’Keefe confessed to the stabbing. The police searched his room and found the knife in his pants pocket. It was just a small penknife with a 3-inch blade, but it was long enough to kill.

Richard O’Keefe was indicted for manslaughter.

Sources:

“Committed for Trial,” Fall River Daily Evening News, May 3, 1872.

“Murder of Peter Kenny by Richard O'Keefe,” Illustrated Police News, May 9, 1872.

“The South Boston Murder,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 6, 1872.

“Terrible Murder in South Boston,” Boston Herald, May 3, 1872.

.jpg)