This week we present a guest post from Shelley Dziedzic of Lizzie Borden: Warps & Wefts, a blog devoted to the Borden murders and the city of Fall River, Massachusetts—"News, articles and photos about The Lady, The Crime, The City and The Era.” Shelly is a member of the Muttoneaters, a group that investigates all things related to Lizzie Borden, and the Pear Essential Players who annually re-enact the Borden Murders at the house where they occurred (now a Fall River bed and breakfast.)

The post, “Murder in the Well”, tells the story of a gruesome murder/suicide from another branch of the Borden family tree.

Uncle Lawdwick and Those “Children Down the Well”

Photography and text by Shelley Dziedzic (all rights reserved)

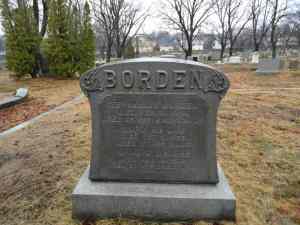

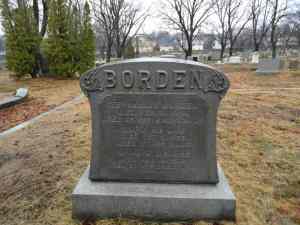

For students of the Borden case, the tale of Lizzie’s great-uncle Lawdwick (also seen as Ludwig, Ladwig, Ladowick and other variations) has long been an interesting footnote to the saga of the Borden murders of 1892. Lawdwick Borden was the son of Martha Patty Bowen and Richard Borden. Lawdwick’s brother Abraham Bowen Borden was Andrew Jackson Borden’s father. Uncle Lawdwick was Lizzie Borden’s great-uncle. He will be referred to as Lawdwick hereafter as that is the spelling which is seen on his grave marker.

Abraham Bowen Borden (Lawdwick’s brother and Lizzie’s grandfather)

Lawdwick would enjoy the company of four wives over the span of his life, not an unusual occurrence in the days when women often died in childbirth or from complications following childbirth. There are records of four marriages:

Maria Briggs, Eliza Darling, Eliza Chace (sometimes seen as Chase), and

Ruhama Crocker. Ruhama Crocker Borden is listed as Lawdwick’s widow in Fall River city directories after Lawdwick died in 1874. The spelling and handwriting in censuses of the period is often poor or illegible, thus creating a challenge for historians generations later to decipher.

It is the second wife,

Eliza Darling Borden who has piqued the excitement of Borden case scholars today, for it is she who did the unthinkable- she killed two of her three children and then took her own life. Today it might be chalked up to post partum depression. She had three children in rapid succession. Even the details of her suicide are clouded over time. Most versions would have it that she went upstairs in the little Cape Cod style house next door south of the Charles Trafton house in 1848, (which would become the Andrew Borden house in 1872) when she was at the age of 37, and sliced her throat with Lawdwick’s straight razor after dropping her children in the cellar cistern. Another version has her committing self-destruction behind the cellar chimney. As thrilling tales often go, they tend to improve and evolve with the retelling.

Paranormal investigators today who visit the Lizzie Borden home, take great pains to attempt to contact these ghostly children who died so tragically years before Abby and Andrew would be done to death by hatchet on August 4, 1892. Guests who stay at the Borden home, now a popular bed and breakfast, leave toys for the “ghost children” in the guest rooms and declare they can hear childish laughter and sounds of play on the second and third floors.

This sad tale has endured for so long due primarily to Lizzie Borden herself- and her trial of 1893. Lizzie was carefully examined to determine if she were mentally competent. Questions were asked as to the sanity of the Borden clan in general. Not surprisingly the topic of Eliza Borden and her unfortunate children was introduced as a possible source of inherited madness. This was quickly shot down as Eliza Darling Borden was only a Borden by marriage, and not a blood relation to Lizzie Borden at all. Mention was made that the sole survivor of the well incident, Maria Borden (Hinckley), was “alive and well and a mother herself still living in the city”. It is a possibility Maria was named for Lawdwick’s first wife, Maria Briggs, as was a common custom in cases of the untimely death of a young spouse upon remarriage of the widower.

But first, the details on all of the family members. Mother of Lawdwick:

Martha Patty Bowen Birth Jul 13 1775 in Freetown, Bristol, Massachusetts, USA , Death Nov 16, 1827

Father:

Richard Borden Birth 1769 in Bristol Co., Massachusetts, USA , Death Apr 04 1824 * note that Richard’s mother was named Hope Cook. Most likely Cook Borden was named for her family surname.

Lawdwick’s Siblings:

Abraham Bowen Borden 1798-1882

Thomas Borden 1800

Amy Borden 1802-1877

Hannah Borden 1803-1891

Richard Borden 1805-1872

Rowena Borden 1808-1836 (stone below)

Cook Borden 1810-1880

Lawdwick 1812-1874 (stone below)

Zephaniah 1814-1884 (stone below)

Lawdwick’s wives:

Maria Briggs married Sept 8, 1833

b. 1811 – d. 1838 (stones below)

Eliza Darling married March 16, 1843

b.1811 – d. 1848 suicide and mother who drowned two of her three children

(engraved

Second Wife)

Baby Holder S. Borden- Drowned

Eliza Ann, aged 2 Drowned

Born October 22, 1844 died 1909 buried under

Maria Borden, no mention of husband Samuel B. Hinckley.

Maria Borden (Hinckley)

(daughter and only living child)

Eliza T. Chace married February 29, 1856 Third Wife

Ruhama Crocker Borden shown living with Lawdwick in 1870 census with sister Lydia and

Maria, Eliza’s daughter now 25 and married to Samuel B. Hinckley, a Civil War veteran on 2 Oct 1866. Ruhama is listed as Lawdwick’s “widow” in Fall River city directories after 1874.

Ruhama Crocker- b. 1814-d. 1879 (in Providence in 1850, living with parents and siblings in 1860 in Attleboro

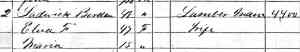

An interesting detail about Maria Borden and her husband Samuel B. Hinckley. Samuel had been a boarder in 1850 at the Lawdwick Borden house when Maria was a little girl of 5. Samuel was 18. The two would wed on October 3, 1866. Samuel had served in the Civil war and was mustered out as a full captain in Washington D.C. on July 14, 1865. (click on image below for full size). In 1850 both Samuel and Lawdwick are listed as “Millers”, presumably in a lumber yard.

At least two more infants are buried in this plot, both near Maria Briggs Borden, which would make them half siblings of the Maria who survived the cistern. One was born the year after Lawdwick’s marriage to Maria Briggs, the other two years later. A name is barely readable on one stone, the other reads Matthew.

Census listing for 1860

Lawdwick is a Lumber man, second wife Eliza T. Chace Borden is keeping house and Maria is now 15. Whatever became of the marriage of Maria and Samuel is unclear. The newspaper article in 1893, during Lizzie Borden’s trial mentions the living child from “the cistern was a mother herself and living in the city”. Maria Borden Hinckley would have been 49 years old at the time of Lizzie’s trial in New Bedford.

My thanks to the groundsmen at Oak Grove Cemetery, Will Clawson, Len Rebello, and Ancestry.com

.jpg)