Saturday, May 27, 2023

With a Butcher’s Keen Blade.

Saturday, May 20, 2023

Murderer Quickly Caught.

The night of September 29, 1892, Paulson’s landlord, William S. Byrnes, saw a man enter Paulsen’s room. Twenty minutes later, he heard a door slam. Then, he and his wife saw a man run out of the house. Byrnes went to Paulsen’s room and found him sitting in a chair with his skull crushed. Paulsen had at least eight deep gashes in his head—blows from an axe.

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Annie Harman and Ephraim Snyder.

Annie Harman (sometimes spelled "Herman") of York County, Pennsylvania attended a singing

party in December 1878. The next morning her body was found by the side of the

road, her skull was crushed, her jaw was broken, her face was badly cut and

bruised, and she was shot through the eye. The prime suspect was Ephriam Snyder

who allegedly seduced Annie and refused to marry her. But the facts did not

match the narrative and the evidence against Snyder was purely circumstantial.

Read the full story here: The Snyder-Harman Murder.

Saturday, May 6, 2023

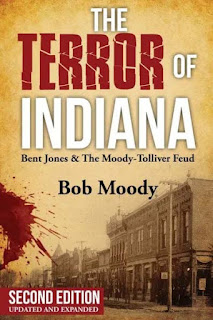

The Moody-Tolliver Feud.

I am pleased to introduce this week’s guest blogger, Bob Moody, author of The Terror of Indiana: Brent Jones & The Moody-Tolliver Feud. Bob is the great-great-grandnephew of Tom Moody, who was murdered during the Moody-Tolliver Feud. He is a retired radio personality, programmer, and corporate VP. Bob served on the board of directors of both the Country Music Association and the Academy of Country Music. He was inducted into the Country Radio Hall of Fame in 2007. Bob and his wife, Karen, live in Jeffersontown, Kentucky.

The second edition of The Terror of Indiana: Bent Jones & The Moody-Tolliver Feud is available at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

For more information: http://www.bobmoody.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/bobmoodybook/

THE MOODY-TOLLIVER FEUD

Date: March 2, 1875

Location: Orleans, Indiana

Victim: Thomas Moody

Cause: Shotgun blasts with poisoned buckshot

Accused: Alonzo “Bent” Jones; Lee Jones; Parks Toliver; Tom Toliver; Eli Lowry

At the subsequent estate sale one of the Toliver boys shouted, “The black-hearted sons-of-bitches have stolen more than they ever brought here!” That resulted in a brawl, with Tom Moody being attacked and seriously injured by four Toliver sons and son-in-law Alonzo “Bent” Jones. Each of the assailants was at least twenty years younger than their victim. This led to a series of lawsuits that only increased the anger as the Moodys prevailed in court and annexed sixty acres of the Toliver family farm.

Shortly after midnight on Sunday morning, June 25, 1871, as the family was sleeping, the Moody farmhouse was firebombed with jugs of burning benzine. A group of unknown assassins surrounded the house and fired at those attempting to escape the flames. Polly suffered severe burns and a hired man was seriously wounded. Tom Moody was climbing a fence to run for help when he was hit with a load of buckshot. The next day’s edition of the New Albany Ledger called it a “Dastardly Attempt to Assassinate a Whole Family.” The attack generated headlines across the U.S. and Great Britain, including a front-page story in the New York Times. It was reported that there was “no possible chance” that Tom would survive his gunshot wounds – but he did.

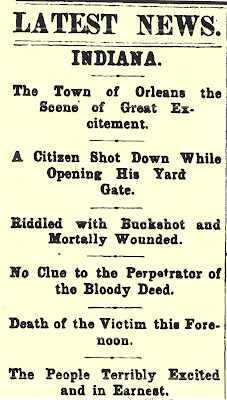

The Moody family hired private detectives to find those guilty of the attempted murders and there were more trials and hearings that served only to build frustration on both sides. Meanwhile, the Moody brothers and Polly sensibly relocated to a two-story house in nearby Orleans. It was claimed that they rarely left home after dark and turned their dwelling into a virtual fortress. After more than three years of threats but no additional violence, Tom Moody decided to participate in a card game at a shop in the Orleans business district on the night of March 2, 1875. After walking home, he stopped to open the gate and someone hiding behind a hedge across the street shot him in the back with both barrels of a double-barreled shotgun. After hours of excruciating pain, he died the next morning.

The Moody family offered a $3000 reward, while the Indiana governor and local officials added another $1600, resulting in a bounty amounting to a total of more than $125,000 in 1923 dollars. That enticed additional self-styled private detectives to arrive in the area. Local citizens were outraged and there were rumors that they might call upon the euphemistic “Judge Lynch.”

While the remaining prisoners were confined in a common cell in the Orange County jail in Paoli, an apparent lynch mob held the sheriff at gunpoint at midnight and took control of the jail. As the mob approached the cell, the prisoners fired out at them from behind bars with a pistol smuggled to them by friends of the well-connected Bent Jones, dispersing the crowd. That episode resulted in a change of venue to Bloomington, where the murder trials began in 1877. The press reported that nearly five hundred people had been subpoenaed to testify and rooms were so difficult to find that some potential witnesses were provided free accommodations in the Monroe County jail. It was an event characterized by elaborate Gilded Age legal orations, with some closing statements reportedly exceeding eight continuous hours. Daily trial updates appeared in major newspapers across the nation.

Bent Jones and his brother, Lee, were quickly convicted of murder in separate trials and were both sentenced to life terms at the Indiana State Prison South, where Eli Lowry was already an inmate. Parks and Tom Toliver were tried jointly in Bloomington the following year, but the jury was deadlocked, and the judge declared a mistrial. Their second trial was held in 1879. Jury deliberations were underway when Parks Toliver was allowed to return to his wife’s rooming house to change clothes, accompanied by a deputy. While his beautiful wife and her sister distracted the guard, the defendant walked out the back door, mounted a horse waiting in the alley – and rode off into the sunset. A posse was quickly summoned to conduct what became a fruitless search. If Parks had waited for a verdict, he would have learned that this jury, too, had been unable to agree, with seven reportedly in favor of conviction and five voting “not guilty”. The judge dismissed the jury on the grounds that one of the defendants could not be present for the verdict. Two years later, amidst complaints about the amount of time and public money already spent on the previous trials, all charges were dropped against Parks and Tom Toliver.

It was later revealed that Parks had made his way to Arkansas, where he was a fugitive until it was safe for him to return home. Now styling himself as Dr. Milton Parks Tolliver, he established a medical practice in Elnora, Indiana, although there is no evidence that he ever graduated from medical school. He outlived three of his four wives and was arrested for selling illegal drugs and operating a phony diploma mill for medical students before his death in 1926. Tom Toliver was shot and killed in 1900 following a dispute over allegedly loaded dice in Washington, Indiana. Eli Lowry worked in the prison office and was on duty when a telegram arrived on Christmas Day of 1890 informing him that he had been pardoned by the governor. Lowry went from prison to a job with the Vigo County sheriff’s office in Terre Haute. That ended when he was accused of being involved in a plot to rob inmates. Lowry died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1895, less than five years after his pardon.

.jpg)