Reverend Jacob S. Harden felt he had been roped into an unhappy marriage by Louisa Dorland and her conniving parents. His new wife threatened his promising career and put a damper on his active social life as well. When the young bride passed away mysteriously, Harden acted like a guilty man but professed innocence almost to the end.

Date: March 9, 1859

Location: Andersontown, New Jersey

Victim: Hannah Louisa Harden

Cause of Death: Poisoning

Accused: Rev. Jacob S. Harden

Synopsis:

Louisa Harden, wife of the Reverend Jacob S. Harden, died on the morning of March 9, 1859, after several days of progressively worsening illness. Harden was preaching at the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mount Lebanon, New Jersey, but, at age 22, he had not fully established himself there and was staying at the home of Dewitt Ramsay in Andersontown. Louisa, who was living with her parents in Mount Lebanon until they could afford to set up a household, had come to Andersontown to spend a few days.

Not long after arriving Louisa became violently ill. The symptoms abated for a day or so, then returned with even more intensity. The night of March 8 she asked for a doctor, but Harden refused. When Ramsay saw Louisa, he also thought she needed a doctor. Harden argued that she did not; Ramsay insisted but by the time a doctor arrived she was dead.

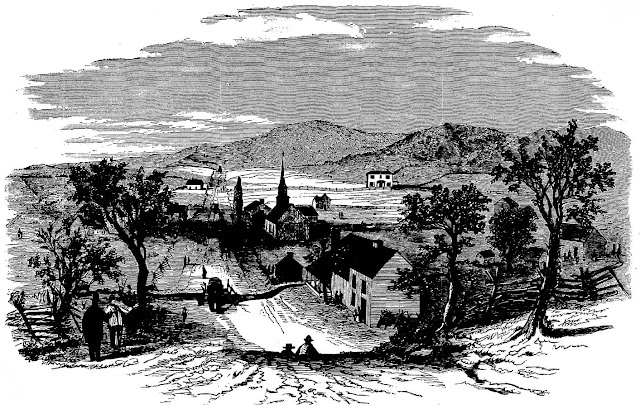

|

| Andersontown, N. J. |

The marriage between Jacob and Louisa Harden had never been a happy one. She was born Hannah Louisa Dorland and they had known each other as school children in Blairstown, New Jersey, but lost touch when the Dorlands moved away. Jacob had gotten the religious call early and at age and at 19 was working as a colporteur, traveling throughout New Jersey selling religious books and tracts. He met Louisa Dorland again in Mount Lebanon and her parents decided that Jacob was the perfect man for their daughter, taking every opportunity to put the two together.

Louisa wanted to make a visit to Blairstown and Jacob agreed to take her. Upon their return, rumors were floating that the two were going to marry. The rumors escalated and people were saying that Louisa had been pregnant and lost the child and that Jacob was the father. The rumors were false, but they threatened his reputation as a man of God, and although Louisa had not been pregnant, the couple did have intimate relations and Louisa pressured him to do the right thing. Finally, Jacob agreed to a conditional engagement—he would marry her in two or three years after he had established himself. It would also give Louisa time to improve her education, a necessity for a minister's wife.

Louisa’s parents would not agree to this and threatened to sue him for breach of promise unless they married immediately. Jacob began to suspect that the parents had started all the rumors themselves. He finally agreed to marry Louisa if the family would draw up a legal contract relinquishing all claims against him and formally denying the rumors. The Dorlands issued and signed the following document and the two were married:

RELEASE.

Know all men by these presents that I, Hannah L. Dorland, of the township of Lebanon, County of Hunterdon, State of New Jersey, have and by these presents do promise, release and forever quit claim unto the Rev. Jacob S. Harden, of the township of Lebanon, County of Hunterdon, State of New Jersey, his heirs, executors, and administrators all and all manner of action and actions, cause and causes of action, suits, bills, bond, writings, obligation, debts, dues, reckonings, account, sum and sums of money, judgments, execution, grants, controversies, trespasses, damages and demands whatsoever, both at law and in equity, or otherwise, howsoever, which against him, the said Rev. Jacob S. Harden, I ever had, now have, or which I, my heir, executors or administrators can, shall or may have, claim, challenge or demand, for or by reason or means of any act, matter, cause or thing from the beginning of the world to the date of these presents.

Witness my hand and seal March 17, 1858.

Hannah L. Dorland.

[Seal.]

Sealed and delivered in presence of

Samuel Dorland, }

Catharine Dorland. }

This is to certify that the matter is satisfactorily settled concerning the rumors in circulation between the Rev. Jacob S. Harden and Samuel Dorland's family.

Samuel Dorland.

March 17, 1858.

By this time, it is safe to say that whatever love Jacob Harden had for Louisa Dorland had disappeared. Louisa, also, was more interested in being married than in being a wife—since they could not afford to set up a household, she elected to live with her parents while he lived in a boarding house. When Jacob became pastor of the Mount Lebanon, M. E. Church he stayed at the homes of several of his parishioners, he and Louisa very seldom saw each other. The two communicated by letters which were often contentious.

In March 1859, the coroner’s jury indicted Jacob Harden for the murder of his wife, but he was still at large. A month later there was still no sign of Hardin until the editor of the Warren Journal received a subscription request that caught his attention. A man named James Austin in Fairmount, a small village near Wheeling in what was then western Virginia, requested a subscription to the paper as he was “… very anxious to learn whether Jacob S. Harden had been indicted for the murder of his wife at the approaching term of court.” The editor was immediately suspicious and sent a copy of Harden’s photograph, along with a copy of the governor’s proclamation offering $500 for his arrest to the police in Wheeling. Before long Jacob Harden was in custody and on his way back to New Jersey.

Trial: April 18, 1860

Jacob Harden’s trial for the murder of his wife was delayed three times, twice because of the absence of prosecution witness, Dr. Chilton, the New York chemist who had analyzed the stomach, and once because of the absence of defense witness, Mrs. Ramsey. The trial finally began on April 18, 1860, with both of the missing witnesses along with at least 175 more. The defense contended that the case was entirely circumstantial and that nothing in Harden’s history suggested he was likely to commit murder. In fact, they said, Mrs. Harden had killed herself. She was not healthy and had been in constant pain, though she hid this from her family. On May 2, the jury returned a verdict of guilty and Jacob Harden was sentenced to hang.

Verdict: Guilty of murder

Aftermath:In March 1859, the coroner’s jury indicted Jacob Harden for the murder of his wife, but he was still at large. A month later there was still no sign of Hardin until the editor of the Warren Journal received a subscription request that caught his attention. A man named James Austin in Fairmount, a small village near Wheeling in what was then western Virginia, requested a subscription to the paper as he was “… very anxious to learn whether Jacob S. Harden had been indicted for the murder of his wife at the approaching term of court.” The editor was immediately suspicious and sent a copy of Harden’s photograph, along with a copy of the governor’s proclamation offering $500 for his arrest to the police in Wheeling. Before long Jacob Harden was in custody and on his way back to New Jersey.

Trial: April 18, 1860

Jacob Harden’s trial for the murder of his wife was delayed three times, twice because of the absence of prosecution witness, Dr. Chilton, the New York chemist who had analyzed the stomach, and once because of the absence of defense witness, Mrs. Ramsey. The trial finally began on April 18, 1860, with both of the missing witnesses along with at least 175 more. The defense contended that the case was entirely circumstantial and that nothing in Harden’s history suggested he was likely to commit murder. In fact, they said, Mrs. Harden had killed herself. She was not healthy and had been in constant pain, though she hid this from her family. On May 2, the jury returned a verdict of guilty and Jacob Harden was sentenced to hang.

Verdict: Guilty of murder

On July 6, 1860, Jacob Harden was hanged in Belvedere, New Jersey. Hundreds of people who had converged on Belvedere to witness the execution were disappointed to learn that the hanging would be held behind the walls of the jail yard and attended by only one hundred fifty ticketed witnesses. The rest waited outside when the trap was sprung the news was relayed outside and the crowd’s cheering filled the air.

On July 6, 1860, Jacob Harden was hanged in Belvedere, New Jersey. Hundreds of people who had converged on Belvedere to witness the execution were disappointed to learn that the hanging would be held behind the walls of the jail yard and attended by only one hundred fifty ticketed witnesses. The rest waited outside when the trap was sprung the news was relayed outside and the crowd’s cheering filled the air.Prior to the execution Harden confessed to the murder but refused to make the confession public. It was later published in a book entitled Life, Confession, and Letters of Courtship of Jacob S. Harden, of the M. E. Church, Mount Lebanon, Hunterdon Co., N. J. In the confession, Harden admitted that he had often wished Louisa dead but had not thought of taking her life until she arrived in Andersontown. He first gave her the arsenic on half an apple. She remarked that there was something gritty on it and he told her it was a powder to prevent pregnancy. Louisa got sick but recovered so he bought more arsenic and gave it to her in glasses of milk. He also gave her a tumbler of laudanum.

Harden said he did not know that the stomach could be analyzed and the poison detected. In fact, he was unaware that poisoning was considered murder and carried the death penalty. As an afterthought, he closed his confession with “Warn the youth of temptation, etc.”

Sources:

“Anderson Town - The Scene of the Wife Poisoning Case.,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 19, 1860.

“Arrest of Jacob S. Harden,” Evening Post, April 23, 1859.

“The Case of Harden,” Centinel of Freedom, May 10, 1859.

“The Case Of Rev. J. S. Harden. ,” Commercial Advertiser, June 30, 1860.

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, April 23, 1859.

“The Harden Poisoning Case.,” Newark Daily Advertiser, May 4, 1860.

“Harden the Wife Poisoner,” New-York Observer, May 10, 1860.

Life Confession, and Letters of Courtship of Rev. Jacob S. Harden (Hackettstown: E. Winton, Printer, 1860).

“Local Matters,” Centinel of Freedom, March 29, 1859.

“The Trial of Jacob S. Harden for the Murder of his Wife,” Commercial Advertiser, April 18, 1860.

“Trial of Rev. Jacob S. Harden,” Newark Daily Advertiser, May 2, 1860.

.jpg)

1 comments :

October 1, 2017 at 5:25 AM

Hitchcock may have been inspired to use the arsenic in the milk method for his movie "Suspicion" with Cary Grant.

Post a Comment