That autumn, Southern proposed to Kate Hambrick, and the two were married. They lived happily for several months until Bob began staying out late without explanations. Kate began hearing rumors that Bob was still meeting with Narcissa. They had been seen walking together in the woods several times since the wedding. The news made Kate intensely jealous.

That Christmas, Kate’s father held a party at his house for the people of Pickens County. In accordance with the hearty hospitality of the country, Narcissa was invited to attend. Kate warned her husband that he must not dance with Narcissa or pay her any attention during the party. She went to Narcissa as well and told her she must not accept or encourage any attentions from Bob if they were offered. Her warnings were disregarded, and as the evening progressed, Bob led Narcissa to the middle of the floor for a dance. Kate tried to cut in, saying he had promised the dance to her. Narcissa refused to leave, and Bob took Narcissa’s side.

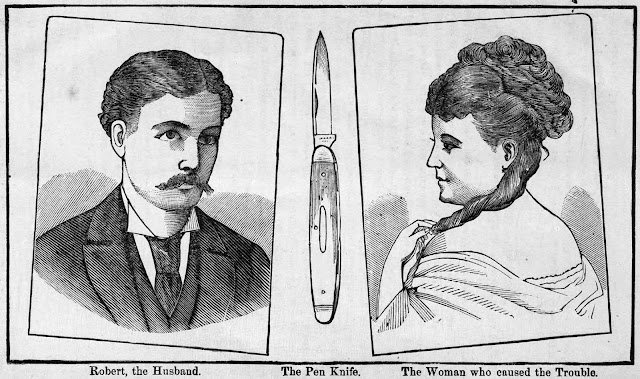

Kate left the room in anger. She went to her father and asked to borrow his pocket knife to pare her fingernails. He thought the request peculiar but gave her the knife. She opened the blade and concealed the knife in her dress. When the dance was over, she caught Narcissa by the arm.

“You have danced enough.” Said Kate as she whipped out the knife and plunged it into her breast. Narcissa staggered back as a stream of blood gushed from the wound. Kate sprang on her, caught her by the hair, then cut her throat almost from ear to ear. Narcissa fell dead.

The room erupted with excitement. Mr. Houly, one of the floor managers, saw the body and shouted, “What man did that?”

“I am the man who did it,” said Kate, “and I don’t regret it.”

Houly ran to the door, locked it, and said no one should leave the room until the matter was investigated and the guilty parties arrested.

Bob Southern, who had been silent to this point, drew a pistol, and, taking his wife by the arm, said, “Gentlemen, I’m going to leave this house, and my wife is going with me; I’m going to do it if I have to shoot through!”

No one stopped them as they went out the door and disappeared into the night. Accompanied by Bob’s father, William, and his brothers, James and Miles, Bob and Kate fled Pickens County and headed north.

Narcissa’s family offered a reward of $250 for their capture, and the governor of Georgia added another $100, but for more than a year, the Southerns remained at large. In February 1878, W.W. Findley, a private detective and ex-sheriff of Pickens County, learned that Bob and Kate, along with Bob’s father and brothers, had settled on a farm in Franklin, North Carolina. By the time Findley and his men got there, they had moved again. The Southerns were traveling by ox cart, and Findley soon caught up with them. They quietly went ahead and set up an ambush, and Findley was able to capture the fugitives without firing a shot. They found Kate Southern nursing a little baby who had been born during their flight.

Bob and Kate Southern were taken back to Georgia. At their request, the father, mother, and baby were held together in the same cell.

The grand jury charged Kate with first-degree murder and her trial was held that May. Kate pled not guilty and sat through the trial with her baby in her lap. Her attorneys were in such disarray that they could not make her case. They knew nothing of the prosecution witnesses so could not challenge them, and they introduced no witnesses of their own. At one point, they halted their case and proposed a plea of insanity. They soon withdrew it amid jeers from the prosecution. At another time, they tried to withdraw the plea of not guilty and plead guilty to manslaughter. This was also rejected.

One observer said, “In making the arguments, the counsel disagreed, and I really believe if there had been no lawyer for the defense, Kate would have been cleared.”

The public was against the execution. Outside of court, Kate has prominent legal advisors who collected affidavits to convince Governor Colquitt to pardon her. First—Kate’s character for chastity, modesty, good nature, religious professions, and practice was fully established by affidavits from the best ladies of the county and her minister. Second—Her nervous and unbalanced condition at the time of the killing was set forth, including one affidavit that showed she had three successive epileptic fits on the Monday before the killing. Third—It was shown that at least two of the jurymen had expressed themselves in favor of having her hung before they went on the jury.

Other petitions and affidavits spoke of Narcissa’s bad character. Her ex-sister-in-law swore that Narcissa “frequently spent the night alone in the room with men in her house and that she has positive knowledge of the fact that she was not only unchaste but grossly so.” Others spoke of the hypocrisy of the “unwritten law” of the South that considered a husband justified in killing his wife’s seducer but would hang a wife for killing her husband’s seducer.

Governor Colquitt took all these arguments into consideration, but a Georgia correspondent of the Chicago Times summed up the situation:

“It is safe, I think to say in advance that she will never be hung. Gov. Smith, our last Governor, dug his political grave by allowing Susan Eberhart to hang, and if Gov. Colquitt is not impressed with the justice of commutation or pardon, he is too much of a politician to not interfere. A young married lady told me to-day that if Colquitt refused to pardon this woman, every married lady in the State would use her influence against him if he was ever a candidate for office again.”

Governor Colquitt commuted Kate Southern’s sentence to ten years in prison.

Sources:

“A Battle for Life,” New York Herald, May 21, 1878.

“The Fatal Dance,” Charlotte Democrat, February 22, 1878.

“The Fury of a Woman Scorned,” Springfield Republican, February 20, 1878.

“Kate Southern,” Chicago Daily News, May 24, 1878.

“Kate Southern's Crime,” Herald, May 6, 1878.

“Love, Jealousy and Murder,” New Orleans Times, February 20, 1878.

“Mrs. Southern's Jealousy,” Augusta Chronicle, May 12, 1878.

“Passing Events,” Cleveland Leader, February 21, 1878.

“A Romantic Murder,” New York Herald, February 14, 1878.

“A Woman to be Hanged,” New York Herald, May 3, 1878.

.jpg)

0 comments :

Post a Comment