Saturday, April 30, 2022

The Nathan Murder.

Saturday, April 23, 2022

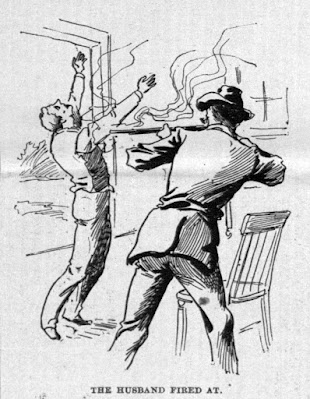

Shot Man and Wife.

On November 18, 1891, their neighbor, William Keck, aged 50, stopped by for a visit. He was carrying a double-barreled shotgun and said he had been out shooting. They invited him to stay for dinner, and Keck accepted. After dinner, William was sitting by the window watching the chickens when, without provocation, Keck grabbed his shotgun and emptied one barrel into William’s back. Jeannette ran from the house screaming, and Keck dragged her back into the cabin, threw her on the floor, and fired the second barrel into her head.

She died immediately, but William was still alive. Keck went to the woodpile, seized an axe, and struck William on the side of the head. Though badly wounded, William was able to wrestle the axe away from him. Keck grabbed a piece of firewood and beat William unconscious.

A few days earlier, Keck had borrowed twenty-five cents from William Nibsh and saw that there was more money in a bedroom drawer. After knocking William unconscious, Keck went to the drawer and took all the money—six dollars, mostly in silver. Relations between Keck and the Nibsh family had always been friendly; robbery appeared to be the only motive for the murder.

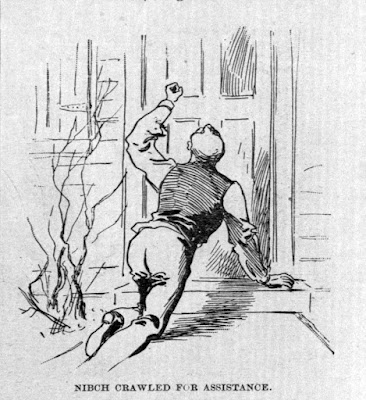

Keck left the cabin and stopped to buy some coal before going home. He paid with silver coins, believed to be from the stolen money.When William regained consciousness, he began crawling to the house of his neighbor, Mr. Druckenmiller, about a hundred yards away. He arrived at the door about two hours after the murder. Druckenmiller spread the word, and a party of men went back to the Nipsh cabin. They found that Keck had returned, possibly to look for more money. The men grabbed him and held him under guard until policemen from the city could arrive.

Before the police arrived, a vigilance committee of at least a hundred men amassed at the cabin and took Keck outside, intending to hang him from the nearest tree. Mrs. Joseph Masonheimer, daughter of the victims, intervened and persuaded the men not to wreak their vengeance on the murderer but to let the law punish him. The police came and took him to jail in Allentown.

William Keck had a bad reputation in Lehigh County and had served several terms in jail. Most recently, he was sentenced to six months in Easton Jail for threatening to kill his wife and daughter. He claimed he was innocent of the Nibsh assault and murder, but when brought to jail, he begged the police to shoot him and end his miserable life.

Under heavy guard, Keck was taken back to Ironton for the coroner’s inquest. William Nibsh, still in serious condition, was sworn in to testify. With great deliberation, he kissed the Bible, then, pointing to Keck, said, “This is the man who shot me, struck and hit me with a club and axe and shot and killed my wife.” Nibsh died shortly after testifying. Keck was charged with two counts of first-degree murder.When Keck’s trial began the following January, the vigilance committee had grown to 200 men, and they occupied seats in the courtroom. They made it known that should the verdict be acquittal, they would mob both Keck and the jury. Keck was still pleading not guilty and now claimed that William Nibsh shot his wife and attempted to shoot Keck. Keck then killed Mibsh in self-defense. When the jury came back, the vigilantes did not have to mob anyone—the verdict was guilty of first-degree murder.

After an appeal and a temporary reprieve to go before the board of pardons—both of which failed—William Keck was sentenced to hang on November 11, 1892. On November 10, Keck cheated the gallows; the guard found him lying dead in his cell. There were no marks of violence and no traces of poison, so the coroner’s jury found that Keck had died of “nervous prostration superinduced by the fear and terror of execution imminent.”

A week later, after a toxicological examination of Keck’s body, the jury had to revise their verdict. Keck had died from ingesting arsenic, probably smuggled in by one of the relatives or friends who visited the jail before the scheduled hanging. They now called the cause of death “arsenical poison, self-administered with suicidal intent.” The jury blamed laxity of prison discipline and called for prompt action and reform.

Sources:

“An Aged Woman Murdered,” Watertown Daily Times, November 19, 1891.

“Daughter's Act,” Evening Herald, November 20, 1891.

“Died of Arsenic, Not Fright,” Pittsburg Dispatch, November 20, 1892.

“Jury and Prisoner to be Mobbed,” Freeland Tribune, January 7, 1892.

“Keck Cheated the Gallows,” Evening Herald, November 11, 1892.

“Keck Murder Trial,” Patriot, January 11, 1892.

“Keck's Poisonous Dose,” Freeland Tribune, November 28, 1892.

“Murderer Keck Convicted,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 1892.

“Murderer Keck in Great Glee,” Patriot, September 2, 1892.

“A Murderer Narrowly Esca[es Lynch,” Patriot, November 20, 1891.

“Nibch Dies from Wound,” Patriot, November 30, 1891.

“The Nipsh Murder,” Patriot, November 23, 1891.

“Shot Man and Wife,” National Police Gazette, December 12, 1891.

“Wife Dead, Husband Dying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1891.

Saturday, April 16, 2022

Rare Photo of America's Youngest Serial Killer.

This week we have a guest post from Donna Wells, a former employee of the Boston Police Department who made a rare discovery—a previously unknown photograph of “The Boston Boy Fiend,” Jesse Pomeroy.

Discovery of Previously Unknown Photograph of America’s Youngest Serial Killer, Jesse Pomeroy

I have a very strange story to tell you. I call it my strange little serial killer story… My name is Donna Wells. I graduated in 1997 from Simmons College in Boston with a master’s degree in library and information science. Several months later, I accepted a position with the Boston Police Department as their first records manager and archivist. I was tasked with establishing and managing the Department’s records management program and also with the day-to-day running of the Department’s records center and archives. I served in this position until 2007 when I took early retirement due to health and personal reasons.

|

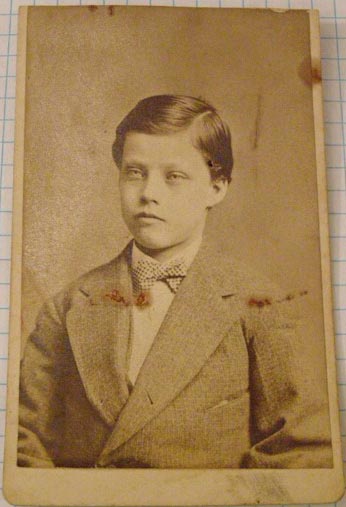

| Jesse Pomeroy Carte de Visite |

I now live in Central Maine with my husband. I am disabled, but I buy jewelry, buttons, and other items at auctions, flea markets, and thrift stores and sell them on eBay.

One day, some time ago, I grabbed a tin of buttons from the shelf and took it downstairs to sort. I opened the tin and, lying on top of the buttons, was an old envelope, all folded up. There was nothing written on the envelope, so I opened it and inside there was an old photograph (a carte de visite) of a young boy. He was kind of creepy looking because the irises of his eyes appeared to be without color – they were a dead white. I put the photograph aside and continued with the buttons. Over the next several days, I was drawn back to the photograph over and over again. It just seemed like I should know who this was – that I had seen a similar image somewhere. And there was something tickling my brain, something about a white eye.

When fourteen-year-old Jesse Pomeroy was arrested in 1874 for the murder of Horace Millen, he was thought to have tortured at least six children and tortured and murdered two more. The two murder victims, ten-year-old Katie Curran and four-year-old Horace Millen had both been stabbed and nearly decapitated. Katie also had a fractured skull and several broken bones. Horace had also been nearly castrated, had one eyeball deeply pierced, and been set on fire. The victims that had managed to survive his attacks had suffered whippings, stabbings, beatings, which included broken noses and split lips, vicious bites to the face and buttocks, attempted castration, and attempted scalping. At the time of his arrest for Horace Millen’s murder, Jesse’s reputation in Boston as the “Boy Torturer” was firmly established.

In the course of my research, I found out that the title and author of the book I had read was Fiend: The Shocking True Story of America’s Youngest Serial Killer by Harold Schechter. I no longer possessed a copy of the Schechter book because I had donated it to the BPD Records Center & Archives. I know my successor at the archives, Margaret Sullivan, so I called her and told her my story. I sent her a scan of the image that I had found and asked her to compare it with the drawing in the book. Margaret thought that the image could be Jesse. She pointed me to some resources, and I dove back into the internet.

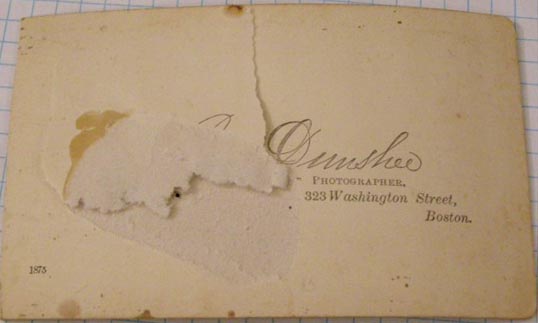

On the back of my photograph, there is a partial photographer’s name. The last name is Dunshee, and there is an address given as 323 Washington Street, Boston. There is also what I assume is the date of the print – 1875 in the lower left corner. There is a very useful database online that lists Boston’s photographers and provides the dates that they would have been at a particular address. The approximate dates that this database gives for when E.S. Dunshee was at the address on the back of my photo are 1873-1874.

|

| Back |

I had ordered another copy of the Schechter book and had read it again to see if I could find anything that would help me to authenticate the photograph. On page 92, I found a quote from a journalist from the Boston Herald:

“He does not look like a youth actuated by the spirit of a fiend, and, with the exception of a peculiarity about the eyes, he has no marked expression in his face from which one might read the spirit within. The idea that he is insane is not supported, except by the extraordinary character of his conduct.”

Contrary to what many reporters of the time of the murders claimed, the image in my photograph does not show a wild-eyed lunatic, neither is there any indication of the monster that he could become, but shows a seemingly normal, although sad and confused, boy with, admittedly, very strange eyes. Looking at my photograph, I am forced to speculate that Jesse’s very normality made it possible for him to succeed in deceiving and assaulting his victims. I mean, if he truly looked like a monster, he would not have been able to get close to his victims.

In my photograph, there does not seem to be any great differences in the visible portions of his actual eyeballs, however, because the photograph is black and white, any differences of color between his irises would not be obvious. I have examined the image under magnification, and the only difference that I can detect is a slightly more “flattish” look to the iris of his right eye. There are, however, several much more obvious external differences – his right eye is more slanted and smaller than his left. Also, there is a dark area around his right eye. It appears to be a bruise of some kind, but whatever it was, it was permanent because it remains in all of the future photographs of Jesse. In later photographs, he does appear to have developed some kind of clouding of his right eye, but in my early photograph, that is not evident.

|

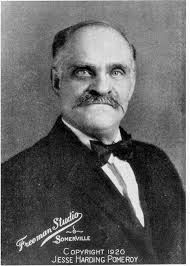

| 1870s Drawing -- Found Photograph |

Dear Donna--

My agent forwarded your email to me.

After closely studying your photograph, I think you may, in fact, have found an early portrait of Jesse Pomeroy. I base that conclusion by comparing it not only to the newspaper engraving of the adolescent Pomeroy reproduced in my book but on the photograph of the elder Jesse that served as the frontispiece of his 1920 book of poems, which I've attached. Take a close look at the right eye in both your photo and the later one: they are virtually identical--weirdly shaped, slightly slanted, distinctly different from the left, and surrounded by a strange dark shadow as if he had a permanent shiner.

It's an exciting find, and I would certainly consider writing it up and trying to get it published somewhere. Thanks for sharing it with me, and let me know if I can be of further help. Best, Harold S.

|

| Jesse Pomeroy, 1920 |

I am still, even now, pretty freaked out about the fact that this photograph, a previously unknown photograph and the only known photograph of Jesse during the period in which he was active, ended up in my buttons, given the fact that I am probably one of the few people who might be able to recognize the subject.

Donna Wells can be reached at TonyMay2021@gmail.com for questions and comments.

Saturday, April 9, 2022

A Triple Tragedy.

The neighbors became alarmed and rushed to the saloon as two more shots were fired. They found Martin Curley lying in a pool of blood with a bullet wound over his left eye, a revolver lying on his breast. Mike Haddock (aka Anton Stanovitch), another Hungarian, lay three feet away with a wound behind his ear. Haddock was dead but both the Curleys were still alive. The neighbors brought them into an adjoining room and summoned physicians. Mary lived another hour and Martin lived for two hours but neither regained consciousness before dying.

It was first believed that Martin Curley had shot both his wife and Mike Haddock then shot himself. Haddock owed $70 in unpaid rent and Mary was rumored to have an intimate relationship with Haddock. Martin had a bad reputation and was known to be a fiend when drunk.

The theory changed when reporters learned that 5-year-old Mamie Curley witnessed the shootings. She said, “There was an awful noise when I was rocking the cradle. I rushed out into the barroom and saw papa and another man falling down. I cried ‘mama,’ but mama didn’t hear me. I saw another man in the backyard.” She did not recognize the other man, but he was believed to be John Thralle. The County Commissioners offered a $500 reward for his arrest and the search for Thralle began.

The police captured Thralle and on January 1, a coroner’s inquest was held. The story changed again when two new witnesses testified. Mathew Daley and Robbie Warner both saw Martin Curley shoot his wife. Thralle testified through an interpreter that he was in the saloon and invited Curley to have a drink of whiskey. Curley said he was not feeling well and did not care for it. The remark led to a dispute resulting in tragedy.

The jury determined that Curley murdered his wife and Haddock, then shot himself. Thralle was released.

Sources:

“The Broderick Tragedy,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, January 1, 1891.

“Four Victims of One Gun,” Chicago Daily News, December 29, 1890.

“Triple Tragedy,” Columbus Dispatch, December 29, 1890.

“A Triple Tragedy,” National Police Gazette, January 17, 1891.

“Wyoming Valley Tragedy,” Delaware Republican, December 30, 1890.

Saturday, April 2, 2022

Who Killed Lottie Morgan?

Hurley, Wisconsin, a tough iron mining town, was the

scene of many brutal crimes, but none more startling than the 1890 murder of

Lottie Morgan. She was an actress who performed in variety theaters in Hurley and the

surrounding area. Though she lived with Johnny Sullivan, a Hurley politician, she was known to have many lovers who kept her supplied with money and jewelry. Her arrangement with Sullivan may have been more about business than

romance.

Lottie Morgan was well-known, well-liked, and

reportedly one of the prettiest women on the range. Lottie was a prostitute,

but newspapers used euphemisms to soften her notoriety—she was a courtesan, a

sporting woman, one of the demimondes, of more than doubtful reputation. The

Montreal River Mine and Iron County Republican said, “She carried herself

with all the propriety possible for her class, was vivacious, sprightly, well

informed, and was universally known here and at Ironwood and Bessemer.”

On the morning of April 12, 1890, the mutilated body

of Lottie Morgan was found in the filthy alley between two low dives on

Hurley’s main drag. She lay in a pool of coagulated blood with a deep gash in

the side of her head, about 4 inches long, from the temple back. At her feet

was her own 32 caliber revolver. A reporter found a bloodstained axe in a

nearby shed, believed to be the murder weapon.

None could find a motive for the murder. Lottie was

fully clothed when found and had not been molested. The police ruled out

robbery because Lottie was still wearing her diamond earrings and other

jewelry, valued at more than $5,000.

One of Lottie’s lovers was an ex-policeman, and some

speculated that she was working as a police spy. The criminals

who discovered her secret took their revenge.

The police and public favored another, more specific, theory. A

recent nighttime robbery at the Hurley Iron Exchange Bank netted the thieves $39,000.

Lottie had been subpoenaed to testify at the trial because the bank’s interior

could be seen from the window of Lottie’s apartment. The court found Ed Baker

and Phelps Perrin guilty of the robbery even without Lottie’s testimony, but

they became the prime suspects in her murder.

Lottie Morgan’s elaborate funeral included a beautiful

display of flowers and a procession featuring a brass band. The town raised

nearly $200 to investigate the crime. A grand jury was convened to uncover the

mysterious plot that led to Lottie’s murder.

But nothing was uncovered. In May, the County Board of

Supervisors offered a $500 reward for the apprehension of the murders, but

nothing came of this either. As time went on, the police and people of Hurley faced newer crimes and Lottie's case went cold. Lottie Morgan’s name disappeared from the newspapers and her unsolved murder was eventually forgotten.

Sources:

“Brained with an Ax,” St Paul daily globe, April 12, 1890.

“Brevities by Wire,” Aberdeen Daily News, April 12, 1890.

“Domestic,” Daily Inter Ocean, April 12, 1890.

“Found Murdered,” Erie Morning Dispatch, April 12, 1890.

“The Hurley Murder,” Bay City Times, April 12, 1890.

“A Hurley Murder,” Duluth News-Tribune, April 12, 1890.

“Lottie Morgan Murdered,” Montreal River Miner and Iron County Republican, April 10, 1890.

“Lottie Morgan's Murder,” Portage Daily Democrat, April 14, 1892.

“Murdering a Woman,” Milwaukee Journal, April 11, 1890.

“News of Wisconsin,” Boscobel Dial, May 26, 1892.

“To Cover a Crime,” Argus-Leader, May 17, 1890.

“Was She an Important Witness?,” Milwaukee Journal, May 14, 1890.

“Who Killed Lottie Morgan?,” Illustrated Police News, April 26, 1890.

“Who Killed Lottie Morgan?,” Detroit Free Press, April 12, 1890.

“Why Lottie was Murdered,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 14, 1890.

.jpg)