Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Scott Jackson.

Saturday, December 25, 2021

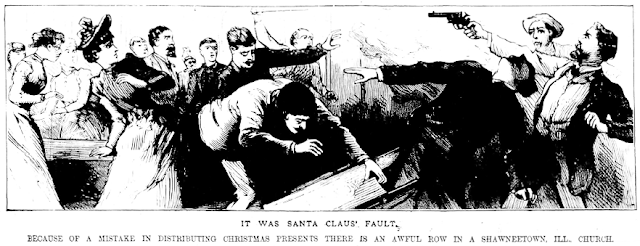

It was Santa Claus' Fault.

Sources:

“A Free Fight in a Church,” Boston Herald, December 26, 1889.

“It Was Santa Claus' Fault,” National Police Gazette, January 11, 1890.

“Wound Up om a Free Fight,” New York Herald, December 26, 1889.

Monday, December 20, 2021

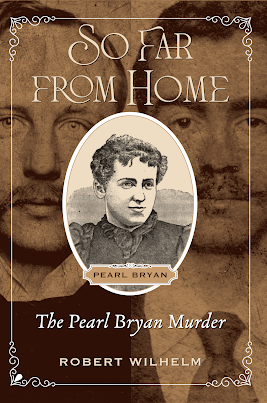

So Far from Home.

New Book!

The Pearl Bryan Murder

Saturday, December 18, 2021

Murder of Col. Sharp.

Saturday, December 11, 2021

Michael M’Garvey.

The evening of November 21, 1828, Michael M’Garvey violently chastised his wife, Margaret, in the room, they occupied on the top floor of a house at the corner of Pine and Ball Alleys, between Third and Fourth Streets, and between South and Shippen Streets in Philadelphia. He tied her by the hair to a bedpost and began beating her, unmercifully with a whip, continuing at intervals for the next hour and a half. When she passed out, he attempted to throw her out the window but pulled her back in when someone outside saw him and cried out.

Saturday, December 4, 2021

The Wife's Lament.

The business was doing well, and the two men got along until O’Keefe moved in. That winter they frequently argued over the way Kenney was treating O’Keefe’s sister. Kenney was a quiet man when sober, but aggressive when drunk, which became increasingly frequent. The arguments sometimes turned violent with punches thrown and bottles broken. Kenney ordered O’Keefe out of the house. O’Keefe refused to leave, and his sister took his side. O’Keefe remained but the two men barely spoke to each other.

At dinner on May 2, 1872, O’Keefe asked Kenney about the store. Kenney had been drinking heavily for several days and O’Keefe worried that it would hurt their sales. Kenney told him to mind his own business, but since the store was O’Keefe’s business, the argument escalated. When the subject of Kenney’s cruel treatment of his wife arose again, Kenney jump up and said, “Come down to the green and we will settle this matter.” Mrs. Kenney interceded then and separated them.

Around 8:00 that night, as Kenney was waiting on a customer and O’Keefe came to the barroom door and looked in. When Kenney was through with the customer, he went outside, and the argument started up again on the sidewalk. A scuffle ensued, they clinched and fell to the ground. O’Keefe pulled a jackknife from his pocket and stabbed Kenney in the neck. Kenney exclaimed, “I am killed.” O’Keefe took off down the alley.

Kenney managed to raise himself from the sidewalk and staggered into the store with blood streaming from his neck. Medical aid was summoned, but O’Keefe had severed Kenney’s jugular vein and he died before the doctors arrived. His wife bent over him, frantically imploring him to speak to her. “Who did this?” she asked, “What did Peter do that they should kill him.” She continued to lament over her husband’s body until someone removed her to a neighboring house.

O’Keefe entered the house through the backdoor, ran upstairs, and changed his clothes. He went back out through the barroom door where officers Dudley and Johnson were waiting for him. At the police station, O’Keefe confessed to the stabbing. The police searched his room and found the knife in his pants pocket. It was just a small penknife with a 3-inch blade, but it was long enough to kill.

Richard O’Keefe was indicted for manslaughter.

Sources:

“Committed for Trial,” Fall River Daily Evening News, May 3, 1872.

“Murder of Peter Kenny by Richard O'Keefe,” Illustrated Police News, May 9, 1872.

“The South Boston Murder,” Boston Evening Transcript, May 6, 1872.

“Terrible Murder in South Boston,” Boston Herald, May 3, 1872.

Saturday, November 27, 2021

A Red Path of Jealousy.

Martha Place, driven by jealousy, strangled her stepdaughter.

Saturday, November 20, 2021

A Boy Murderer.

Wesley took the infant, splattered with blood, out of the room, and cleaned and dressed her. Then he hitched up the buggy and started for his grandfather’s house, stopping on the way to tell the neighbors that an assassin had murdered his parents; he took the baby and they fled for their lives.

The neighbor went to the Elkins’s house where they found the bodies of 45-year-old Mr. Elkins and his 25-year-old wife. Mr. Elkin’s head had been blown to pieces, and Mrs. Elkin’s head was beaten to a jelly. They sent for the police who were immediately skeptical of Wesley’s story.

|

| Wesley Elkins, around the time of the murder |

John Wesley Elkins was indicted for first-degree murder. At his trial the following January,

|

| Wesley Elkins, after his release. |

Wesley was believed to be the youngest person to date to be sent to prison in America, and his life sentenced prompted heated arguments. Some felt that no 11-year-old boy belonged in prison regardless of the crime, others felt that Wesley should be sent to the gallows.

Wesley Elkins used his time wisely while at Anamosa. He worked at the prison library and at the chapel and became proficient with the written and spoken word. In 1902, twelve years into Wesley’s sentence, after bitter debate Governor Cummins issued him parole papers. Wesley left the prison a free man.

Following his release, Wesley led a full life. He first settled in St. Paul, Minnesota where he worked on the railroad. Then in 1922, he married a Hawaiian woman in Honolulu. Eventually, he became a farmer in San Bernardino, California, where he resided until his death in 1961.

Sources:

"A Boy Murderer." Evening Star 27 Jul 1889.

"A Brilliant Beginning." National Police Gazette 9 Nov 1889.

"A Young Fiends' Confession.." New York Herald 20 Oct 1889.

"Double Murder by a Boy." New York Herald 27 Jul 1889.

"Murdered his Father and Mother." Daily Illinois State Register 27 Jul 1889.

Anamosa State Penitentiary: The Strange Case of Wesley Elkins.

"To Prison For Life." Kalamazoo Gazette 23 Jan 1890.

"Wesley Elkins." Wheeling Register 13 Jan 1890.

Saturday, November 13, 2021

Most Horrible Crime of the Age!

William Bachmann was last seen alive at a brewery owned by Charles Marlow and Marlow was quickly arrested for Bachmann’s murder. But prosecuting Marlow would prove difficult because there were no eyewitnesses to the crime, there was no identifiable body, and Marlow’s mother-in-law, under oath, had already confessed to the murder.

Read the full story here: The Marlow Murder.

Saturday, November 6, 2021

Hamilton Y. Jones, Detective.

At 8:00 the next morning, George Powers’s dead body was found lying under the table with a bullet wound in the side of his head. A hole in the window near the table indicates that the shot was fired from outside. The murderer then broke out a back window, sash and all, and entered the room. Powers was still alive, and a fearful struggle ensued. His hands were covered with mud as if he had caught hold of the killer’s boots. The killer then beat Powers’s brains out with a club.

The killer rifled through Powers’s trunk and turned his pockets inside out, but the only thing taken was his pocket watch. The description of the stolen watch was remarkably detailed: a silver open-face watch, No. 14,122, with case No. 15,399, Hoyt movement, key winder. That day, $1,000 was raised to prosecute the search for the killer.

The killer or killers were believed to have been among a group of tramps seen around Marshall that week. Their identity remained unknown until September 14, when someone from Marshall recognized them in St. Louis. William. Lyons, alias Kerr, John J. Schanner, William Staab, and William Gagon were arrested on suspicion but later released.

The early afternoon of October 26, Chief of Police Phillips of Springfield, Illinois, received the following dispatch:

Lincoln, Ill., October 26 – Arrest a man, smooth face, black overcoat, black stiff hat, low heavy set. Wanted for murder. On freight due at 2:30 this p.m.

Jones.

Though the police did not know who Jones was, they arrested the described man as he descended from a boxcar. The man said his name was Martin Cratty, and among his effects were letters and papers addressed to that name. One letter, signed Kittie O’Brien, was suspicious. It spoke of a scheme and said Cratty had been recommended as one who could do the work and keep it secret.

When the 3:50 passenger train arrived from the north, the police learned the identity of Mr. Jones, and they were none too happy. It was Hamilton Y. Jones, a self-styled detective that they knew well. “He is a notoriously hard character,” said the Daily Illinois State Journal, “and is as familiar with the walls of our county jails as he is with a drink of whiskey, and that is putting it pretty strong.”

Jones produced a warrant for the arrest of A.C. Kerr and stated that Martin Cratty was an alias. He was wanted for the murder of George Powers in Marshall. Jones claimed that Cratty had pawned Powers’s watch in Lincoln the previous day. Cratty claimed he had purchased the watch from a jeweler in Bloomington and had the dealer’s certificate at home. Jones said he had been working the case for over a month and had captured the killer. From the State Journal again, “Hamilton, however, is a liar of proportions that Baron Munchausen never dreamed of and is a man whom the police regard as a sneak thief and petty crook of the worst stripe.” The police tended to believe Cratty’s story, but to be on the safe side, they held him in jail.

Jones left but planned to return on October 30 to take charge of the prisoner and return to Marshall. In the meantime, the police recovered the pawned watch and found it was not Powers’s—it had a Millan movement, not a Hoyt movement, and neither of the numbers matched. Cratty’s stepfather arrived in Springfield with a statement from Cratty’s employer proving he was in Bloomington at the time of the murder.

Hamilton Jones returned to Springfield on October 30, and as soon as he entered the police station, he was arrested for the false imprisonment of Martin Cratty. Cratty was released, and Jones occupied his old cell.

When his investigations began, Hamilton Jones convinced authorities in Marshall that he was on the right track. They furnished him with $15 cash, a pair of handcuffs, and a good revolver. From time to time during his travels, Jones telegraphed for more money which Marshall provided. On November 12, Jones was arrested in Marshall for securing money under false pretense.

On December 15, Hamilton Y. Jones was arrested again in Springfield on an unrelated matter. He was charged with impersonating a United States Post Office Inspector and stealing mail. This time he would serve a term in the penitentiary.

The murder of George Powers remained unsolved.

Sources:

“Arrested for the Powers Murder,” Chicago Daily News, October 27, 1886.

“Deeds of Blood,” Juneau County Argus, September 23, 1886.

“A Foul Murder,” Daily Illinois State Journal, September 14, 1886.

“Hamilton Y Jones' Vagaries,” Daily Inter Ocean, December 16, 1886.

“Illinois,” Indianapolis Journal, November 11, 1886.

“Martin Cratty,” Daily Illinois State Register, October 29, 1886.

“Minor Mention,” Daily Illinois State Register, November 12, 1886.

“A Mysterious Murder,” National Police Gazette, October 2, 1886.

“News Article,” Daily Illinois State Journal, October 28, 1886.

“A Rough Experience,” Daily Illinois State Journal, October 27, 1886.

“See Saw, See Saw,” Daily Illinois State Journal, October 30, 1886.

Saturday, October 30, 2021

The Insanity Dodge.

Insanity was seldom a popular defense to murder -- while defense attorneys used terms like temporary insanity, transitory frenzy, and monomania, to the press and the public it was “the insanity dodge.” The first successful use in America of temporary insanity as murder defense was the trial of Dan Sickles for the 1859 murder of Phillip Barton Key. Sickles appeared perfectly sane at his trial but claimed that his wife’s infidelity had temporarily made him unable to tell right from wrong.

Here are a few cases using the insanity dodge with varying degrees of success:

|

Dan Sickles's Temporary Insanity. 1859 - First successful use of the temporary insanity plea in America. |

|

The Worst Woman on Earth. Lizzie Halliday unsuccessfully pled insanity for the murder of her husband and two servants in 1893. She was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to the electric chair but the governor commuted her sentence and sent her to an insane asylum. There she murdered her nurse. |

|

Crazy John Daley. John Daley, known as “Crazy John," pled insanity for the axe murder of his wife in 1883 and was easily acquitted. “Daley became a homicidal maniac through a frenzy of religious excitement.” Said the press. |

|

Shot by a Jealous Husband. When Daniel Monahan shot his wife for adultery in 1886, the public viewed the murder as justified. He was acquitted on the grounds of insanity and the verdict was well received. |

|

Transitory Frenzy. Charles Henry was obsessed with actress Effie Moore. She led him on for a few weeks, but when he learned she was already married he shot her. He pled not guilty by reason of “transitory frenzy”; to everyone’s surprise, the verdict was not guilty. |

|

A Contract with the Devil. Joseph E. Kelley murdered Joseph Stikney during an 1897 bank robbery. He pled guilty but during sentencing medical experts described him as “A high-grade imbecile” “about 8 or 9 years old, mentally and morally.” Their diagnoses saved him from the gallows but he was sentenced to thirty years in prison. |

Saturday, October 23, 2021

Veiled Murderess!

Despite the judge’s admonitions, Henrietta Robinson covered her face with a black veil as she stood trial for murder. Everything about the defendant was a mystery—her motive for murder, her behavior before and after the crime, and even her true identity. It was well known that “Henrietta Robinson” was an assumed name, but who she really was has never been determined.

Saturday, October 16, 2021

Michigan Double Murder.

A very anxious and excited man arrived at the jail in Ann Arbor, Michigan, around midnight, October 22, 1871. He told the jailer he was unwell and wanted to sleep in the jail that night. The jailor decided it was in everyone’s best interest to give him what he wanted. As he locked the cell door, the man burst out crying but would not say why. The following morning the jailor released him.

The man, Henry Wagner, went to see his brother August and declared that he thought he had murdered his wife. “I don’t know what I have been doing,” he said, “I don’t know whether she will live or not.” They went to the police and gave Officer Leonard the key to Wagner’s house so he could check on the wife’s condition.

Wagner’s wife, Henrietta, ran a fancy store with her partner Mary Miley. Henry, Henrietta, and Henrietta’s 3-year-old son Oscar lived in the back room of the store. What Officer Leonard saw when he opened the door to their room nearly froze his blood. Mrs. Wagner lay on her side in her nightdress; her head was a mass of pounded flesh and bone. Around her, spatters of blood and clots of bloody gore covered the walls and nightclothes. Nearby laid a bloody hatchet—she had been beaten with the blunt end. After several minutes, the officer heard a slight rustling in the bed. He pulled back the covers to find little Oscar covered with blood; his head had been smashed, but he was still alive. Leonard notified the coroner and arrested Henry Wagner. Oscar died a few hours later.

The Wagners had come to Ann Arbor from Germany about three years earlier. At the time, they were unmarried; Henrietta was the ex-wife of Henry’s older brother, Oscar’s father, who was still living in Germany. Henry and Henrietta married the previous July, but at times it was an unhappy marriage—they would have serious arguments, sometimes ending in violence. Despite the fighting, Henry declared he had always loved his wife very dearly.

24-year-old Henry Wagner related what had occurred the night of the murder to a reporter who visited him in jail:

“For the past two or three days, we lived most happily; she never seemed to love me so much. Last night she went to bed, I don’t know what time. I said to her good night and went to the bed to kiss her when she spit in my face and kicked me, saying, go away, you are a crazy man, and I can’t live with a crazy man. I said to her, give me my money, and I will go. She said nothing to this. I then went and got the money and started to leave, when she jumped up and said, ‘I will cut you in pieces before you go with that money.’ That made me very angry, and I took the hatchet from the wood-box and went toward her, she jumped at me and called me a dog, and told me to leave the house. I kept brandishing the hatchet to frighten her. She and the child both cried fire and murder, and as she clutched me by the throat, I hit her accidentally. She fell right down and said, “Oh my,” and groaned. When I saw what I had done, that she was hurt so she could never get well, I thought I would put an end to her life and struck her several times. After this, I remember nothing. I seemed to see my wife before my eyes all the time. I don’t remember striking the boy at all. I remember putting out the light and locking the door. I went out in the street, but I could not go anywhere I did not see my wife just as I struck her, lying before my eyes. I came down to the jail, but I could not sleep or eat. I don’t know what I shall do.”

At the inquest the following day, August Wagner testified that the trouble between Henry and Henrietta was due to the child. Henrietta had been the prostitute of their older brother in Germany. They had several children together, and he called her his wife, but they were never married. He believed that Henry was Oscar’s father, but Henry did not acknowledge this.

Mary Miley testified that Henry was very jealous of Henrietta and the trouble between them began about two weeks after their wedding. Mary said he had willed Henrietta all his property, including money still in Germany. A written contract giving her all his money, some $3,000, was found in Henry’s pocket, torn in two.

The newspapers speculated correctly that Henry Wagner would try “the insanity dodge” at his trial the following March. Friends, coworkers, and clergymen testified that Henry always seemed excited and uneasy, speaking in a disconnected manner, frequently disparaging his wife’s character. August Wagner said that the family always considered him of unsound mind.

The defense had no professional witnesses to give medical testimony as to the state of Henry Wagner’s mind, but the prosecution did. Professor Palmer, a specialist in insanity, visited Wagner in jail several times and conversed with him. He testified that Wagner did not show any signs of insanity or anything to indicate homicidal impulse. Drs. Lewitt and Kapp also examined Wagner and agreed that he was perfectly sane.

The jury deliberated for two hours then found Henry Wagner guilty of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison in solitary confinement and hard labor.

Sources:

“Conclusion of the Wagner Murder Case,” Detroit Free Press, March 16, 1872.

“The Double Murder At Ann Arbor,” Jackson Citizen Patriot, October 24, 1871.

“A Startling Murder,” Vermont Union, November 3, 1871.

“The Trial of Henry Wagner,” Michigan Argus, March 22, 1872.

“The Trial of Wagner,” Michigan Argus, March 15, 1872.

“The Wagner Murder,” Detroit Free Press, March 13, 1872.

Saturday, October 9, 2021

“Thus She Passed Away.”

Saturday, October 2, 2021

A Great Burly, Broad-Shouldered Bully.

He was also quite fond of whiskey. He was drunk on the night of January 29 when he was working as a bouncer at the saloon. He overheard the assistant barkeeper, A.V. Lawrence, make disparaging remarks about Wieners’s wife to the Head Barkeeper. Wieners responded, drawing his revolver and threatening to kill Lawrence.

A.V. Lawrence, alias Lawrence Mack, was known as a quiet, inoffensive young man, a short man of slight build. He was no match for Billy Wieners. A bystander stepped in to separate them, and Wieners agreed to go home. But before Wieners left, the altercation renewed, and Wieners struck Lawrence in the face with his fist. Lawrence picked up a soda bottle to hurl at Wieners, but before he could throw it, Wieners drew two pistols and fired one, hitting Lawrence in the neck. He died almost instantly.

Wieners was quickly arrested, and the following October, he was tried for first-degree murder. He was found guilty and sentenced to hang on December 14. As the judge pronounced the sentence, Wieners smiled pleasantly and seemed unconcerned, but later, he told reporters he would starve or kill himself before he would meet death on the scaffold. After five months of incarceration, Wieners had already lost 70 pounds.

Wieners received a stay of execution while his lawyer appealed the verdict before the Missouri Supreme Court. They alleged that the judge in Wieners’s trial did not instruct the jury regarding murder in the second degree. At issue was whether Wieners acted with premeditation and malice aforethought in killing Lawrence. Wieners’s attorney argued that he had acted in the heat of passion and should not be charged with first-degree murder. The Supreme Court upheld the verdict. They summed up their lengthy ruling by saying, “We have carefully examined the record to find evidence tending to mitigate the offense of which the defendant was guilty but have failed to discover a circumstance to indicate it was other than deliberate murder.”

The hanging was rescheduled for February 1878. As Billy Weiners awaited his punishment, his sister Annie worked to have his sentence commuted to life in prison. She circulated a petition and met personally with Governor Phelps. While support for commutation was growing, the Governor would not commit himself.

Billy Wieners was hanged at 8:30 AM on February 1, 1878, in the jail yard in St. Louis in front of a small group of spectators, mostly reporters and attorneys. Wieners made a brief speech in which he admitted to killing Lawrence, but not in cold blood. He said he was crazed with liquor, and he warned all men against whiskey and bad associations.

Sources:

“Brutal Murder at St. Louis,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, January 30, 1877.

“Deliberate Murder,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 30, 1877.

“Execution of Wieners at St. Louis,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, February 2, 1878.

“Jottings By Telegraph,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, January 14, 1878.

“Missouri,” Rock Island Argus, February 1, 1878.

“Murder,” Illustrated Police News, February 17, 1877.

“Murderer Sentenced,” Arkansas Gazette, October 31, 1877.

“News Of the Day,” Alexandria Gazette, January 30, 1877.

“A Second Stay,” Chicago Daily News, December 15, 1877.

“Sentence of Death,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 31, 1877.

“Telegraphic Notes,” Milan Exchange, February 8, 1877.

“Wieners Must Hang,” State journal, January 18, 1878.

Saturday, September 25, 2021

Very Pathetic and Truly Remarkable.

In the autumn of 1882, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, Nicholas L. Dukes learned that his fiancée, Lizzie Nutt, had been intimate with other men. Dukes broke his engagement to Lizzie in a letter to her father, Captain A.C. Nutt, accusing Lizzie of promiscuity. Grievously insulted, Captain Nutt confronted Dukes setting off a family feud that resulted in two murders and two controversial trial verdicts.

Read the full story here: A Matter of Honor.

Saturday, September 18, 2021

Edward H. Rulloff.

Read the full story here: The Man of Two Lives.

Saturday, September 11, 2021

Shot by Her Stepson.

“Shortly after 5 o’clock, I came from the kitchen and was putting oil in my lamp when my stepson, Thomas McCabe, fired a shot at me. I fell on my hands and knees and he said, ‘I done it! I done it!’ I said, ‘Why, Tom; why did you do it?’ He said nothing In reply, but stooped over me and took the contents of my pocket. I said, ‘it’s the money of the Land League,’ of which my husband is an officer. He also took my watch and an opera chain. I than said, ‘Oh, Tom; oh, Tom, don’t take my watch and chain!' He said, ‘I will take It; I want money to leave the city.’ I said, ‘Oh, Tom, don’t leave me, I never will mention your name. I will say I fell if you will only lift me up.’ He said, ‘I am not able,’ Then he left me. I called for help. I was paralyzed and could not get up, but after a long while Mrs. Whaley came In, and my stepson threw the pistol into his uncle’s bed. I saw him do it. When he went out be locked the door. I knew of no reason except that be wanted to rob me, I never had an angry word with him of late.”

Thomas McCabe bought a new suit of clothes with the money he stole from his stepmother, then went to a shooting gallery in the Bowery. He was practicing pistol shooting when the police arrested him.

McCabe had come with his father and stepmother from Ireland about four years earlier. He enjoyed life in New York, “but his tastes did not run in orderly grooves.” He did not like the discipline of school, was often truant, and caused trouble for his teachers and parents. His father would have whipped him many times, but for his stepmother’s intervention—she was thought to be too forbearing with him.

He finally got a job as a messenger for the District Telegraph Company but was often absent from this as well. McCabe was fired from the job but was afraid to tell his parents. Instead, he decided to rob them and leave town. When arrested for shooting his mother, McCabe showed no remorse.

At his trial the following September, Thomas McCabe was represented by William Howe of the firm Howe and Hummel, the most successful criminal lawyers in New York. McCabe’s plea was insanity. Under Howe’s cross-examination, McCabe’s father said Thomas had been weak-minded since birth, and at the James Street School, a Christian Brother had sent him home because he could make no progress with his studies and because he had “head trouble.” He was a boy of very weak intellect and was afflicted with epileptic fits.

Howe was not able to win an acquittal but was able to reduce the charge to second-degree manslaughter. Recorder Smyth, who presided over the case, was unhappy with the verdict and said this to McCabe as he handed down the maximum sentence:

“McCabe, the jury in your case took a more lenient and merciful view of your crime than your cowardly action deserved. They might well have rendered a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree on the evidence, and you would have been at the bar of this Court answering with your life for the life you have taken. You were most ably defended, and you have already had all the protection and mercy that ought be bestowed on you. The sentence of the Court is that you be confined in State Prison for seven years.”

Sources:

“A Boy Matricide,” New York Herald, September 20, 1882.

“The Boy Murderer Sentenced,” Evening Star, September 29, 1882.

“City News Items,” New York Herald, July 12, 1882.

“Duties Neglected For A Convention,” New York Tribune, September 21, 1882.

“A Fatal Shot,” Evening Bulletin, May 16, 1882.

“Gotham Gossip,” Times-Picayune, May 19, 1882.

“The M'Cabe Trial,” Truth, September 26, 1882.

“Morning Summary,” Daily Gazette, May 15, 1882.

“Seven Years for a Life,” New York Herald, September 30, 1882.

“Shot by Her Stepson,” Cambria Freeman, May 19, 1882.

“Thomas McCabe,” National Police Gazette, June 10, 1882.

“The Trial of Thomas M' Cabe,” New York Herald, September 26, 1882.

Saturday, September 4, 2021

Slain at the Alter.

At the wedding of James Baptiste and Marie Dujoe, on the Jamisen Plantation, near Thibodeaux, Lousiana, on February 2, 1886, the lights were suddenly extinguished, leaving the room totally dark. Wedding guests sat stunned as screams rang out through the darkness. The lamps were relit revealing that the groom had been stabbed seven times and lay dying on the floor. An investigation soon revealed that Baptiste had been murdered by Keziah Collins, a former paramour—but not soon enough to prevent Keziah from escaping aboard the steamboat Alice LeBlanc.

Sources:

“Slain at the Altar by his Former Mistress,” Illustrated Police News, February 27, 1886.

“State News,” Donaldsonville Chief, February 13, 1886.

“State News,” Donaldsonville Chief, March 6, 1886.

Saturday, August 28, 2021

The Fate of a Seducer.

Read the full story here: A Weight of Grief.

Picture from Illustrated Police News, February 8, 1872.

Saturday, August 21, 2021

Caused by Jealousy.

L.P. Christiansen was the proprietor of the Vienna House in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1888. William E. Bell was the head cook at the hotel until August of that year when Christiansen fired him for paying too much attention to his niece, Annie Christiansen.

L.P. Christiansen was the proprietor of the Vienna House in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1888. William E. Bell was the head cook at the hotel until August of that year when Christiansen fired him for paying too much attention to his niece, Annie Christiansen. Christiansen was not exactly acting to protect his niece’s virtue; he had eyes for Annie himself. L.P. scandalized the Vienna house when he left his wife and persuaded Annie to run away with him to Omaha. With her husband gone, Mrs. Christiansen brought back William Bell to help run the hotel. The two soon became intimate, causing further scandal at the Vienna House.

Mrs. Christiansen and William Bell were soon at each other’s throats. She fired him again and left for Omaha to find her husband. Before she left, Bell told her, “If you bring Christiansen back with you, I’ll kill him.” Despite the warning, Mrs. Christiansen returned to Kansas City with her unfaithful husband.

As soon as Bell learned that Christiansen had returned, he started for the hotel. He was heard muttering, “If he makes a move, I mean to blow him to hell. I’ve stood this razzle long enough and will end it tonight.”

Bell entered the hotel by the rear stairway leading to the second floor and made straight to Christiansen’s room. He drew a 32-caliber bulldog revolver and fired twice— the first shot hit the wall above Christensen’s head, the second struck him in the forehead above the right eye. Mrs. Christiansen opened the door when she heard the first shot, and as her husband fell, bleeding, at her feet, she shrieked, “Oh, God! Will, you are a murderer—you’ve killed my husband!”

Bell ran outside to the pavement and raised the still-smoking revolver to his head. He fired and instantly died. L.P. Christiansen died later that day without regaining consciousness. Mrs. Christensen denied that she had been intimate with Bell and blamed it all on the love of the two men for Annie Christiansen.

Sources:

“Double Tragedy,” Cheyenne daily leader, March 10, 1889.

“A Sensational Tragedy,” Daily Inter Ocean, March 10, 1889.

Saturday, August 14, 2021

Piper and his Crimes.

Thomas Piper murdered three, including 5-year-old Mabel Young.

Read the full story here: The Boston Belfrey Tragedy

Saturday, August 7, 2021

A Baltimore Borgia.

She was planning a trip to Europe in July 1871, and that June, Mrs. Wharton entertained several houseguests. On June 23, General William Scott Ketchum, an associate of her late husband and a longtime family friend, arrived at her house intending to stay a few days. The following day, the general was taken sick and was attended by Dr. P.C. Williams.

As General Ketchum lay ill, Mr. Eugene Van Ness, Mrs. Wharton’s friend and financial advisor, called to spend the evening. She served him a glass of beer, which she said contained a few drops of gentian, a strong tonic to aid digestion. Soon after, Mr. Van Ness became violently ill and had to remain in her house. His physician, Dr. Chew, was summoned to his bedside.

General Ketchum died on June 28, and his sudden death along with the unexpected illness of Mr. Van Ness raised suspicions of foul play. Ketchum’s friends had his remains removed to Washington, where Professor William Aiken of Maryland University analyzed the contents of his stomach. Dr. Aiken reported that General Ketchum’s stomach contained twenty grains of tartar emetic, a toxic compound—fifteen grains are sufficient to cause death. The police determined that Mrs. Wharton had purchased sixty grains of tartar emetic on June 26.

|

| Gen. William Scott Ketchum |

A warrant was issued against Mrs. Wharton for the murder of General Ketchum and the attempted murder of Mr. Van Ness. Deputy Marshal Jacob Frey managed to catch Mrs. Wharton before she left for Europe, and he put Elizabeth and Nellie Wharton along with their two servants under house arrest. At first, it was believed that the servants were responsible, but on July 15, the Grand Jury indicted Elizabeth Wharton, and she was held in jail without bail.

Mrs. Wharton owed General Ketchum $2,600, and between his death and the time of her arrest, she visited his son and tried to convince him that the debt had been paid and that Ketchum was holding government bonds of hers worth $4,000. Her financial situation was considered to be the motive of the murder.

Others, however, believed that Mrs. Wharton was affected with “poisoning mania” because four people had previously died mysteriously in her household. Her husband and son, both heavily insured, had died several years earlier; her son was exhumed, but no poison was found in his body. Her sister-in-law, Mrs. J. G. Wharton, alleged that her husband and son had been poisoned by Mrs. Wharton. She believed that Elizabeth Wharton had murdered her husband—Elizabeth’s brother—because of a $2,500 debt.

Mrs. Wharton’s attorneys asserted that she could not get a fair trial in Baltimore and were granted a change of venue. On December 4, 1871, the trial of Elizabeth Wharton for the murder of General William Scott Ketchum opened to a packed courtroom in Annapolis, Maryland. Eighty-nine witnesses were subpoenaed to testify for the prosecution or defense; the majority of these were physicians and chemists who would give expert testimony.

The defense challenged the assertion that the substance in General Ketchum’s stomach was correctly identified and proposed that he may have died from a natural cause, such as cholera morbus or spinal meningitis. The technical testimony on both sides continued for weeks, and more than one newspaper commented on how tedious the trial became. At the trial’s end, the Baltimore Sun said, “Her trial has occupied forty-two days, in which time theories of chemistry and medicine have been exhausted, as well as the law and the practitioners of all three of these learned professions.”

The case was given to the jury on January 24, 1872, and they deliberated throughout the night. At one, they appeared deadlocked at four for conviction and eight for acquittal, but by 10:00 the next morning, they were in agreement and returned a verdict of not guilty.

Mrs. Wharton was acquitted of the murder of General Ketcham, but she was not yet free. The prosecution intended to try her for the attempted murder of Eugene Van Ness and released her on $5,000 bail until the trial the following April.

The Van Ness trial was continued several times and was not held until January 1873. It lasted nearly a month but did not generate the same excitement as her first trial. The jury deliberated from January 31 to February 3 before announcing they were hopelessly deadlocked. The trial ended in a hung jury.

In April, the prosecution announced that they would stet the cases, meaning that it was not closed, but they would not pursue it at that time. Mrs. Wharton was never retried.

Saturday, July 31, 2021

Jealousy and Murder.

At closing time, Cora returned and was very drunk. Barrett took her home and spent the night in her room at the brothel. Cora was still angry, and around 6:00 that morning, three pistol shots were heard coming from Cora’s chamber.

When the police arrived, they burst into the room and found Barrett lying on the bed with blood flowing from a bullet hole near his temple. Cora lay next to him, her arm around him, with two bullet wounds in her head. On the bed between them laid a seven-shot revolver. She had shot John Barrett in the head, then turned the gun on herself and fired twice.

|

| Cora Young |

Cora did recover, and the following November, she was tried for murder. The case was given to the jury at 4:00 on November 17, 1877. As Cora's jury deliberated, the court heard the case of William Barr, a prisoner at Auburn State Prison who had killed a guard with a snow shovel. That case was interrupted at 6:00 when the jury returned with a verdict in Cora’s case.

"Not guilty," said the foreman; the courtroom erupted with loud applause and Cora fainted. In the confusion that followed, Barr tried to escape, and after several minutes of struggle with the Sheriff’s officers, he was subdued. Barr was put in shackles, and his trial resumed.

Sources:

“The Auburn Murder-Lunatics in Prison,” New York Tribune, February 7, 1877.

“Confusion in a Murder Trial,” New York Herald, November 18, 1877.

“Double Tragedy,” Cincinnati Daily Star, June 15, 1877.

“Jealousy, Murder, and Suicide,” Illustrated Police News, June 30, 1877.

“Murder and Suicide,” Plain Dealer, June 15, 1877.

Thursday, July 29, 2021

New! The Bloody Century Audiobook.

|

pervaded nineteenth-century America marked by lurid newspaper accounts and remembered in ballad and verse. The Bloody Century presents 50 of the most intriguing murder cases from the archives of American crime. It is a collection of fascinating stories—some famous, some long-buried—of Americans, driven by desperation, greed, jealousy, or an irrational bloodlust, to take another’s life. The Bloody Century audiobook, narrated by Charles Huddleston, augments the true accounts of these murders with musical performances of period ballads and poems. |

Listen to a sample chapter:

"Hang Down Your Head, Tom Dula"

The Bloody Century Audiobook

Available from Audible and Amazon

Saturday, July 24, 2021

The Poison Fiend.

Saturday, July 17, 2021

A Cowardly Lover.

On October 28, 1893, Lottie paid a call at the home of Bosworth Morgan in Osawatomie. As she stood by an open window that night, she did not see Jap Rainey sneaking toward the house. He approached the window, then raised his pistol and made good on his promise. He fired into the house, killing Lottie Jackson, then escaped into the darkness.

Everyone knew who did it, and they quickly formed a posse to track him down. Their intentions were clear; when they caught Rainey, they planned to lynch him on the spot. Realizing his position was hopeless, Jap Rainey went to the police station in Paola, Kansas, and gave himself up. This was not enough for the residents of Greasy Bend, who organized a mob of 75 men to travel to Paola, break Rainey out of jail, and lynch him.

Rainey remained safe in the Paola jail until his trial in February 1894. He tried a plea of temporary insanity, but the jury did not buy it. Rainey was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang. He moved for a new trial, but the judge overruled the motion. When Rainey asked for mercy, the judge replied that even if such were meted, there was but one sentence possible under the jury’s verdict. He sentenced Rainey to one year in the penitentiary, then, whenever the governor should so will it, to be hanged.

The governor was not in a hanging mood, and as of December 1898, 46 men, including Jap Rainey, were on death row in Kansas, awaiting execution. In October 1913, after serving 19 years at the penitentiary, Jap Rainey met with pardon clerk S.T. Seaton and fell on his knees, pleading for Seaton to bring about his release. Seaton promised to do so, and that is the last we hear of Jap Rainey.

Sources:

“Current Events,” Muskegon Chronicle, October 28, 1893.

“The Death Penalty,” Topeka Weekly Capital, December 30, 1898.

“Gave Himself Up,” Tyrone Daily Herald, October 31, 1893.

“Jealous Rage,” Indianapolis Sun, October 28, 1893.

“Killed his Sweetheart,” Albany Ledger, November 3, 1893.

“March of Avengers,” Pittsburg Daily Headlight, October 31, 1893.

“A Murder At Osowatomie,” Topeka Daily Capital, October 28, 1893.

“Murder in the First Degree,” Topeka Daily Capital, February 17, 1894.

“Murdered his Sweetheart,” St. Joseph Weekly Gazette, March 13, 1894.

“Murderer Rainey Still Safe,” Lawrence Daily Gazette, November 1, 1893.

“Water at Penitentiary,” Topeka state journal, October 25, 1913.

Thursday, July 15, 2021

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Transitory Frenzy.

Saturday, July 3, 2021

The Body of Mena Muller.

A man gathering leaves in Guttenberg, New Jersey, on May 13, 1881, discovered the body of a young woman with a fractured skull. It took five days to identify her as Mena Muller of New York City. She left her husband then illegally married Martin Kinkowski. That marriage ended badly after Mena and Martin shared a bottle of wine.

Read the full story here: The Guttenberg Murder.

Illustration from Wedded and murdered within an hour!, Philadelphia: Barclay & Co., 1881

Saturday, June 26, 2021

The Outraged Father.

Sources:

“Record of Tragedies,” Mower County Transcript, January 3, 1883.

“Shot his Daughter's Seducer,” Illustrated Police News, January 20, 1883.

“Territorial News,” Butte Semi-weekly Miner, January 6, 1883.

“Territorial News,” Griggs County Courier, April 13, 1883.

.jpg)