Saturday, December 31, 2022

The Murder of Ellen Lucas.

Friday, December 23, 2022

Baltimore Sorrow.

Thursday, December 22, 2022

The Best Books We Read this Year.

So Far from Home: The Pearl Bryan Murder

Included in

THE BEST BOOKS WE READ THIS YEAR (2022)

a collaborative book list by the reviewers at IBR in which they review the best books they read this year irrespective of their publication date. It consists solely of books by indie presses and indie authors.

Saturday, December 17, 2022

The Snyder-Harman Murder.

Reuben Snyder’s 26-year-old brother Ephriam was also at the party. Annie and Ephriam had been going together, off and on, for several years but lately had been arguing. Annie left the party around 8:00 that night. Ephriam left a few minutes later.

The next morning, Annie Harman’s body was found by the side of the road, about a quarter mile from her home. Her skull was crushed, her jaw broken, and her face badly cut and bruised. Next to the body lay a bloodstained chestnut club. A few feet away was another bloodstained piece of wood.

Ephriam Snyder became the prime suspect. Rebecca Snyder, Ephriam’s sister-in-law and Annie’s cousin, reported that Annie told her she thought she was pregnant and did not know what she would do if Ephriam did not marry her. Ephriam refused to marry her; he was engaged to someone else. Annie threatened to take him to court.

The attorneys gave their closing arguments on May 2. W.H. Kain, for the defense, addressed the jury for an hour and twenty-five minutes. He was followed by E.D. Ziegler, for the defense, who spoke for an hour and fifteen minutes. After lunch H.L. Fischer, for the commonwealth, spoke for two hours. Before giving the case to the jury, the judge addressed them for an hour.

The jury deliberated from 4:30 to 6:00 before returning a verdict of not guilty. Ephriam Snyder heartily shook the hand of each juryman and each member of his defense team before leaving the courtroom.

It was not the legal oratory that swayed the jury, one of the jurymen noticed something that even the prosecution missed. The bullets in the cartridge box were a perfect plane, while the bullet found at the scene was concaved. This was enough to convince the jury that the cartridges were not the same as the bullet. Without that, there was not enough evidence to convict Ephriam Snyder of murder.

No one else was ever arrested for Annie Harman’s murder, but the scene of the crime became a center of local superstition. A large shirt was seen stretched at full length in the top limbs of a high hickory tree. The soiled garment was known throughout the region as the “Bloody Shirt.”

Sources:

“Ephraim Snyder's Trial for Murder,” The Philadelphia Times, April 28, 1879.“The Herman Murder,” The York Dispatch, December 10, 1878.

“The Herman Murder,” York Democratic Press, January 3, 1879.

“Miss Annie Herman and Ephraim Snyder,” Illustrated Police News, January 11, 1879.

“News Article,” Juniata sentinel and Republican., December 18, 1878.

“Not Guilty,” The York Dispatch, May 2, 1879.

“A Queer Mark,” The York Dispatch, April 2, 1880.

“Snyder-Harman Murder,” The York Dispatch, April 29, 1879.

“Snyder-Harman Murder,” The York Dispatch, April 30, 1879.

“Snyder-Harman Murder Trial Ended,” The York Daily, May 3, 1879.

“The Snyder-Herman Murder,” The York Daily, December 13, 1878.

“The Snyder-Herman Murder,” The York Dispatch, December 17, 1878.

“Snyder-Herman Murder Trial,” The York Daily, April 28, 1879.

“York County Murder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 13, 1878.

“The York Tragedy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 17, 1878.

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Saturday, December 10, 2022

The Cold Spring Tragedy.

Saturday, December 3, 2022

The Trial, Life and Confessions of Charles Cook.

When tried for the 1840 murder of Catherine Merry, Charles Cook pled innocent by reason of insanity. Despite a history of medical treatment for extreme melancholy, and strange behavior such as running through the streets of Schenectady, wearing nothing but a blanket, proclaiming himself to be the Savior of the world, the jury rejected his plea and found him guilty.

Before his execution, Cook issued a formal written confession elaborating on his mental condition: “I labored upon the control of a single passion, it was that of sexual fondness; and whenever frustrated in my attempts to gratify it, the spirit of revenge came upon me.”

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Howe and Hummel.

|

| Museum of the City of New York |

William Howe and Abraham Hummel were the most successful

criminal lawyers in Gilded Age New York. With a combination of skill,

showmanship, and unethical practices, they defended most of the city’s significant

criminals and many of its murderers. Whether they won or lost, Howe and Hummel

made every trial sensational.

Here are a few of the many accused murderers defended by Howe and Hummel:

| Defendant | Victim | Year | Story |

| James Logan | Charles M Rogers | 1869 |

The Rogers Murder. |

| Jacob Rosenzweig | Alicd Bowlsby | 1871 |

The Great Trunk Mystery. |

| Billy Forester | Benjamin Nathan | 1871 |

Who Killed Benjamin Nathan? |

| Edward Reinhardt | Mary Reinhardt | 1879 |

The Silver Lake Mystery. |

| Thomas McCabe | Catherine McCabe | 1882 |

A Boy Murderer. |

| Dan Driscoll | Breezy Garrity | 1886 |

Murder Among the Whyos - Part 1. |

| Daniel Murphy | Dan Lyons | 1887 |

Murder Among the Whyos - Part 2. |

| Hannah Southworth | Stephen Pettus | 1889 |

Avenging Her Honor. |

| Mickey Sliney | Robert Lyons | 1891 |

The Confessions of Mickey Sliney. |

Saturday, November 19, 2022

An Impossible Suicide.

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Murderous Assault.

Nettie Brown (or Braun) kept a house of ill-fame in St. Louis with her partner and bartender George Hobbs (or Haubs). In 1877, Lizzie Fields was one of their girls. Lizzie and Nettie had been as close as sisters at first, but they were bitter enemies by April. Lizzie gave Nettie a ring of hers for safekeeping; the trouble began when Lizzie saw her ring on the finger of George Hobbs. After a heated argument, they threw Lizzie out of the house, keeping her clothes and the ring.

Lizzie Fields took up residence in a nearby brothel run by Gussie Freeman. On April 3, 1877, Hobbs was walking down the alley near Freeman’s house when Lizzie began shouting vile names at him through an open window. Hobbs paid no attention at the time, but later, he and Nettie went back to Freeman’s to see her. Lizzie taunted them again from the window, and Hobbs picked up a rock and threw it at her. He missed Lizzie but broke the window and tore the curtain.

They went to the door, but Gussie would not let them in. Hobbs explained that he wanted to pay for the window he had just broken, so Gussie opened the door. As they argued over how much the repairs would cost, Nettie rushed in and found Lizzie in the front room. Nettie pulled a butcher knife from her sleeve. Lizzie was holding a soda bottle and was ready to use it as a weapon. Accounts differ as to what Hobbs did next; he either tried to separate the women or held Lizzie’s wrist so Nettie could strike. In either case, Nettie plunged the butcher knife into Lizzie’s chest twice. Then, she and Hobbs ran from the house.

Gussie Freeman sent a messenger to fetch a doctor, and others ran from the house following Nettie and Hobbs. The police arrested the couple soon after. Lizzie held on to life until May 15. The cause of death was a secondary hemorrhage brought on by the ulceration of knife wounds. Nettie Brown was charged with first-degree murder and George Hobbs as an accessory.

The trial of Nettie Brown began on February 15, 1878. Her plea was self-defense, claiming that Lizzie threatened her with the soda bottle. Her attorney also asserted that the secondary hemorrhage was brought on by the large dose of morphine Lizzie had taken that day. He claimed she was nearly dead already when the stabbing occurred.

The jury deliberated for twenty-four hours before telling the judge they were hopelessly deadlocked—9 for acquittal, 3 for conviction. The problem was they were given only two choices, acquittal or first-degree murder and Missouri juries were reluctant to send a woman to the gallows.

In May, State’s Attorney Beach wanted to change the charge to second-degree murder. However, the defense insisted that she be tried on the original charge. Beach argued that such a trial would be useless as no jury would convict a woman of murder in the first degree. The judge agreed to the new charge and the defense requested a continuance.

The case was continued several more times before being tried in April 1879. Nettie Brown was found guilty of second-degree murder and sent to Jefferson City Penitentiary. George Hobbs case was continued generally, meaning the charges were effectively dismissed unless the state found new evidence.

Sources:

“Arraignments,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 9, 1877.

“Criminal Court - Judge Jones,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 30, 1878.

“Criminal Notes,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 11, 1879.

“Disagreement of a Jury in a Murder Case,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 20, 1878.

“Four Courts Notes,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 11, 1879.

“In the Hands of the Jury,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 18, 1878.

“Life in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 6, 1877.

“Murderous Assault on a Woman,” Illustrated Police News, April 22, 1877.

“Nettie Brown's Case,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 16, 1878.

“The News,” Rolla Herald, April 5, 1877.

“Probable Murder,” Evansville Journal, April 4, 1877.

“St. Louis in Splinters,” St, Louis Globe-Democrat, May 4, 1879.

“Stabbed and Killed,” Weekly Globe Democrat, May 24, 1877.

“Trial of Nettie Brown,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 16, 1878.

Saturday, November 5, 2022

Love and Law.

- The tragic love affair between Charles Kring and Dora Broemser ended in one maddened instant—he asked her to leave her husband, she refused, he shot her dead. The prosecution of Charles Kring for the crime of murder lasted eight years, included six trials, and required a ruling by the United States Supreme Court.

Saturday, October 29, 2022

The Confession of Myron Buel.

“Oh my stars! Oh my Stars!” said Buel, apparently horrified.

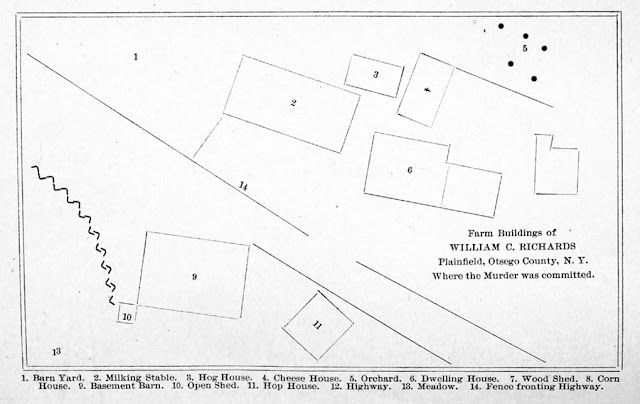

They went to the farmhouse to notify the family. Both Mr. and Mrs. Richards were away that day, so they took Catherine’s sister Maggie and the housekeeper to the barn. Maggie asked Buel what had happened to Catherine, and he said the bull must have killed her.

Buel repeated this several times and it became the accepted story until the coroner got a look at the body. He concluded that Catherine had not been gored by the bull, someone had strangled her and hit her in the face with a blunt object. He also found evidence that she had been raped.

Myron Buel became the prime suspect in Catherine’s murder. Buel was called “The Boy Murderer” but he was 20 years old in 1878. He was madly in love with Catherine, though she was six years younger. He had asked her to marry him, and when she refused, Buel made improper suggestions, driving her to tears. Though he always recanted later, he continued making lewd comments until Catherine threatened to tell her parents.

On the day of the murder, when Buel and Bowen were working in the hops field, he told Bowen that the rubber boots he was wearing were too hot and he went back to the house to change them. He was gone for about 45 minutes. When Bowen asked what took him so long, he said he had to put away a horse that had gotten loose.

Buel was charged with murder and brought to trial on February 17, 1879. The trial lasted ten days and the courtroom was crowded with spectators each day. Following the closing arguments, the judge spoke for an hour and a half, giving instructions to the jury. The jury deliberated for four hours before returning a verdict of guilty.

Buel’s lawyers moved for a new trial on the grounds that the judge had instructed the jury to find him guilty of first-degree murder or acquit him. He should have instructed them on the several degrees of manslaughter as well. The motion was denied, and the judge sentenced Myron Buel to be hanged on April 18.

The execution date was changed to November 14 to allow Buel’s attorneys to argue before the Court of Appeals. The Court refused to grant a new trial and affirmed the judgement of the lower court. They petitioned the Governor for a reprieve, but he refused.

Throughout the process, Buel maintained his innocence but, three days before his execution, with no hope left, Buel confessed to his spiritual advisors and his counsel. In his confession, Buel said he was angry because Catherine had told her parents about his “passionate desire” for her. On the day of the murder, he knew Mr. and Mrs. Richards would not be home. When he told Bowen he was going to change his boots, he was going to kill Catherine.

“Oh! How I felt as I went down the path to the barn!” Buel confessed.

He found Catherine in the cheese house, playing with her kittens. He had let out the calf, knowing she would help him bring it back to the barn. When they were inside the barn, he shut the door and quickly threw a rope around her neck and pulled it tight.

“Her eyes looked terrible when she was struggling,” said Buel, “Then I struck her with a milking stool that stood by me. I then ravished her. She was dead but warm when I committed the crime.”

He carried her to the bull’s stall so it would appear that the bull killed her, then he let the bull out.

“I loved Catherine and was jealous. I intended to kill her and ravish her because I was mad.”

Myron Buel was hanged on November 14, 1879. The gallows in New York State at the time used a counterweight to jerk the condemned man upward. At 10:39 a.m. the body shot four feet up in the air and fell back with a sickening thud. Fourteen minutes later Drs. Westlake and Hills pronounced him dead.

Sources:

“Buel Confesses,” WEEKLY FREEMAN, November 14, 1879.

“The Gallows,” Daily Gazette, April 19, 1879.

Gordon W. Treadwell, Myron Buel the Boy Murderer (Birmingham: Republican Print, 1879.)

“Hanging of Myron A. Buell,” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1879.

“The Murder of Miss Richards,” New York Times, June 29, 1878.

“Myron A. Buell,” The Brooklyn Daily Egal, November 15, 1879.

“Probable Murder,” New York herald., June 28, 1878.

“A Ravisher Held for Murder,” Fall River Daily Herald, July 3, 1878.

“To be Hanged,” New York Herald, March 1, 1879.

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Minerva Dutcher.

Saturday, October 15, 2022

Mysterious Murder in Baltimore.

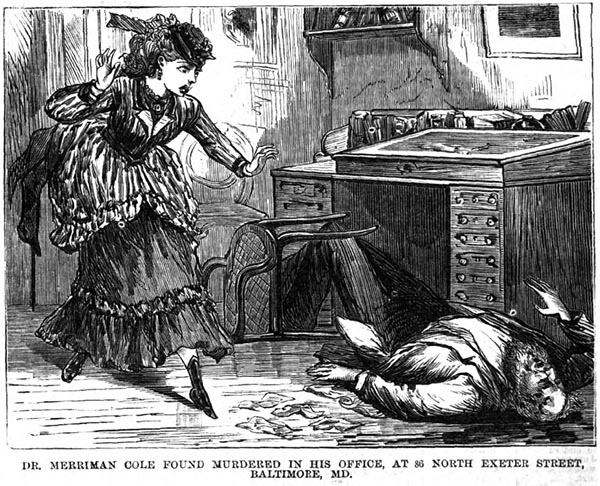

Dr. Merriman Cole was a retired physician with an office in

the heart of Baltimore. In 1872, he was 73 years old and living off the income

from his rental properties. Cole’s daughter went to his office on the evening

of January 6 and found him dead on the floor. He had thirteen wounds about the

head and face and his skull was crushed in three places, apparently with a

hammer.

One of his pants pockets was torn out but the motive was not

robbery. About nine dollars were scattered over the floor and twenty-four

dollars were found in his wallet. It was a Saturday, the day he collected rents

on his properties. On his desk was an unfinished receipt. The police suspected

one of his tenants as his killer. By Monday they had several suspects in custody,

but their names were not made public.

The early suspects were released, and no further arrests were

made until the following September. On September 21, the police arrested

Charles R. Henderson in Baltimore. Henderson was a printer who was one of Cole’s

tenants. He changed his residence shortly after the murder, and the Baltimore Police

had been following him night and day since. The prosecuting attorney waited

until he was sure of conviction before arresting Henderson, and the police

believed they had a strong case of circumstantial evidence against him. On

October 8, the grand jury indicted Charles R. Henderson for the murder of Dr. Merriman

Cole.

Henderson’s trial did not begin until the following June.

Apparently, the evidence against him was not as strong as it first appeared.

The brief newspaper report on the trial said only, “The case was submitted to

the jury without argument and in five minutes they brought in a verdict of not

guilty.”

No one was ever convicted of Dr. Merriman Cole's murder.

Sources:

“Another Horrible Tragedy,” Chicago Tribune, January 8, 1872.

“Dr. Merriman Cole found Murdered in his Office.,” Illustrated Police News, January 18, 1872.

“Merriman Cole Murder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 6, 1873.

“A Murderer Traced Out,” Pittsburgh Daily Commercial, September 24, 1872.

“Murderers in Maryland,” Herald, June 3, 1873.

“Mysterious Murder in Baltimore,” New York Tribune, January 8, 1872.

“News and Gossip,” Paterson Daily Press, September 23, 1872.

Saturday, October 8, 2022

Frank C. Almy.

Saturday, October 1, 2022

The Walton-Matthews Tragedy.

The shooter ran down 3rd Avenue, and Pascall followed, raising the alarm, shouting, “murder!” Several men heard the call and joined the chase. At the front of the pack was John W. Matthews, a well-known railroad contractor. Matthews was closing in as they neared 16th Street. The killer turned, drew his pistol, and fired, hitting Matthews in the chest. In the confusion that followed, the killer dropped the pistol and made his escape.

The men lifted Matthews and carried him to a nearby drugstore, but he died in their arms before he reached it. Walton was still breathing and was taken to Bellevue Hospital, but he died at 8:30 the next morning.

None of the witnesses recognized the shooter, but Pascall was convinced it was John Walton’s stepson, Charles Jefferds. About a year earlier, Walton’s wife died, leaving him with two daughters. About six months later, Walton married a widow named Ellen M. Russell. She told him she had been married twice before, but both of her husbands were dead. She had two sons from the first marriage, Charles and Edwin Jefferds, aged 22 and 19, respectively. She had one son, Frank Russell, 12, from her second marriage. She also said she had adopted her sister’s four-month-old daughter. After the wedding, they all lived together in a house on 23rd Street.

Ellen Russell was an attractive woman; Walton believed her to be a fine, upstanding person. This opinion would soon change. He “observed transactions of a suspicious character on the part of his wife” and decided to make some inquiries. He learned that at least one of her former marriages had ended in divorce, and the husband was still living. Additionally, she had a third husband, a Mr. Morrison, between Jeffers and Russell, who was living in Ohio, and it was doubtful that they ever had a legal separation. Walton also learned that the four-month-old was not the daughter of Ellen’s sister but her own illegitimate offspring.

The New York Atlas called Mrs. Walton “a woman fond of money, luxury and intrigue.” Comparing her to Emma Cunningham, who murdered Dr. Harvey Burdell three years earlier, they called her “…one of those smart, intriguing adventurers of the Mrs. Cunningham school, who are constantly laying in wait to trap wealthy middle-aged bachelors and widowers.”

Soon after the marriage, Mrs. Walton’s eldest son, Charles Jefferds, began misbehaving. He drank heavily and brought unsavory people back to the house. Walton objected, scolding both mother and son. This only made them angrier, and several times Charles threatened Walton’s life.

After several months of this, Walton decided the marriage was over and resolved that they separate. He rented a smaller house on 23rd Street for Ellen and her children, and he moved into the room over the store. He rented the big house to someone else. This angered Ellen and her sons even more since the separation would mean the end of Walton’s wealth. Charles and Edwin continued to harass Walton. On one occasion, Charles showed Walton a pistol which he said he had bought to shoot him. At another time, Walton suddenly took sick and believed he had been poisoned. He changed his will, leaving the bulk of his estate to his daughters, to make it less likely that he would be murdered for his money.

The double murder created quite a sensation in New York City. The mayor offered a $500 reward for the arrest and conviction of the killer. Walton’s estate added another $1,000 to the reward. The police began a manhunt for Charles Jefferds. Jefferds, who fled to Long Island, learned they were looking for him and decided it was safer to turn himself in. The Monday after the murder, Jefferds surrendered to the police but declared his innocence.

The coroner began an inquest into the murders. Among the many witnesses were Richard Pascall, who positively identified the pistol found at the scene as the one Charles Jefferds had used to threaten Walton, and Ellen Walton, who testified that there was no animosity between her son and her husband. The inquest lasted two weeks, and although there was little evidence against Jefferds, he was charged with first-degree murder.

The prosecution was reluctant to bring the case to trial because of the lack of evidence. After an eight-month delay, ignoring two regular terms of the Court of Oyer and Terminer, Jefferds's attorney moved, unsuccessfully, for his client’s release. The trial for the murder of John Walton finally began on June 10, 1861, and lasted about a month. Though nearly everyone believed that Jefferds was guilty, the evidence against him was so thin that no one was surprised that the jury found him not guilty.

After being free for six months, Jefferds began to get cocky. At an impromptu meeting in the 25th Street store with John Walton’s brother, William, Jefferds said, “Do you know who I am? I am Charles Jefferds, the man who murdered your brother, and I can shoot you as quick as I shot him.”

William Walton asked Jefferds for the details of the murder, assuring him that he had been acquitted and could not be tried again. Police Detective Moore, who was also present, confirmed that Jefferds could not be retried. Jefferds told them that he had gone out that night specifically to kill Walton. It was after Walton had a quarrel with his mother, and she offered Jefferds $2,000 to kill her husband.

They were correct in telling Jefferds he could not be retried for Walton’s murder, but Jefferds had forgotten that he was also charged with murdering John Matthews. The new confession was enough for the district attorney to take that case to court.

The trial for the murder of John Matthews began on December 18, 1861. This time the testimony of William Walton and Detective Moore was enough to convince a jury. Jefferds was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death.

The law at the time stated that Jefferd had to serve one year in prison before he could be executed, and after that, the date would be set by the governor. During that time, his attorney tried unsuccessfully to appeal the verdict. But as of May 1868, more than six years later, Jefferds was still on death row at Sing Sing Prison.

On May 15, 1868, Charles Jefferds was found dead in the stable loft of the prison. He had five axe wounds on his body, any one of which could have been fatal. Jefferds had been unwell the day before and was allowed to skip dinner and do some light work at the stable instead. He had been reading a book in the hayloft when he was attacked.Two inmates who had been chopping wood in the work yard, Thomas Burns and George Whittington, were charged with the murder. Burns and Jefferds had been enemies because Burns had caught Jefferds in the commission of what was called “a beastly crime” and “an infamous crime against nature” and reported it to other inmates. The following December, Burns was found not guilty, and charges were dropped against Whittington.

In February 1869, the New York World published a long article saying that a detective using the pseudonym “Jefferson Jinks” had spoken with Jefferds before his arrest. He claimed that, after a few drinks, Jeffereds declared that he had murdered Dr. Harvey Burdell three years before and provided intricate details of the crime.

The murder of Dr. Burdell had caused a sensation in New York and was one of the first great murder cases to be followed nationwide. The World article was reprinted or summarized in newspapers throughout America. However, Jefferds’s confession, if he made it at all, was not likely to be true. The matter was soon forgotten.

Sources:

“An Atrocious Double Murder,” BOSTON HERALD., July 2, 1860.

“Another Chapter in Metropolitan Crime,” New York herald., July 2, 1860.

“Conviction of Charles M. Jefferds,” NEW-YORK OBSERVER., January 2, 1862.

“The Eighteenth Ward Murders,” New-York Daily Tribune., July 4, 1860.

“From New York,” Sun, March 9, 1863.

“Horrible Tragedy,” Commercial Advertiser, July 2, 1860.

“Investigation of the Murder in Sing Sing Prison,” New-York Tribune., May 18, 1868.

“Jefferds Gone to State Prison,” New York dispatch. [volume], May 8, 1864.

“The Jefferds Murder,” World, May 25, 1868.

“Mayor's Office, New York, July,” Evening Post, July 13, 1860.

“Murder in Sing Sing State Prison,” Evening Post., May 15, 1868.

“News Article,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, June 6, 1868.

“Supreme Court,” Journal of Commerce, jr., November 8, 1862.

“Trial of Charles M. Jefferds,” World, July 11, 1861.

“Verdict in the Walton Matthews Murder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 20, 1860.

“The Walton and Matthews Tragedy,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, July 14, 1860.

“The Walton Tragedy,” NEW YORK ATLAS., July 8, 1860.

“The Walton-Mathews Murder,” New York herald., February 24, 1861.

“The Walton-Mathews Murder,” New York Herald, July 12, 1861.

“The Walton-Mathews Murder,” Evening Post, April 8, 1864.

“The Walton-Mathew's Murder,” Evening Post., December 19, 1861.

“Will Of The Late John Walton,” Boston Courier, July 9, 1860.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

"Horrors on Horror's Head."

Dr. Henry Kendall was shot in the head by persons unknown. He was caught in the act of stealing a body from a graveyard in Onondaga, New York, in 1882.

Read the full story here: A Grave-Robber's Fate.

Saturday, September 17, 2022

A Harum-Scarum Creature.

The residents of Rockford, Illinois, Nellie C. Bailly's hometown, remembered her well. When they learned she was accused of murder, the Rockford Daily Gazette reported, “In youth, she was always a harum-scarum creature, and the prediction then made that she would come to no good appears to have been fulfilled.”

Read the full story here: Nellie C. Bailey.

Saturday, September 10, 2022

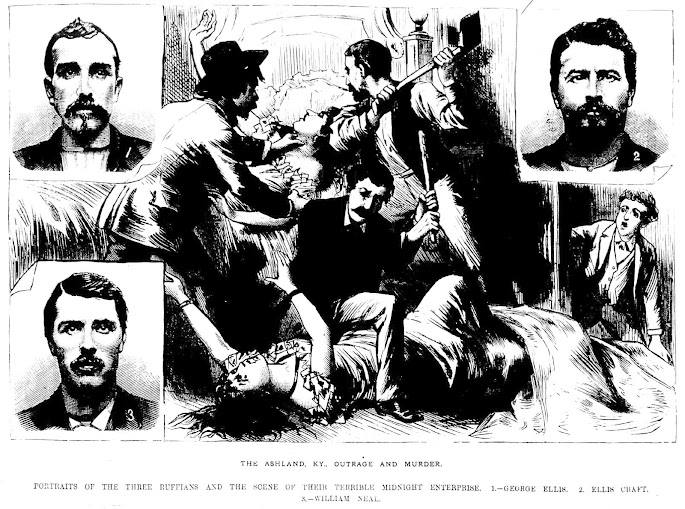

The Ashland Outrage.

Mrs. J.W. Gibbons was away from her home in Ashland, Kentucky, on December 23, 1881. She left behind her 18-year-old son Robert, her 14-year-old daughter Fannie, and 17-year-old Emma Thomas (aka Carico), who was staying with them. Mrs. Gibbons returned the following day to find her home burned to the ground and all three inhabitants dead.

Saturday, September 3, 2022

Clemmer's Hypnotic Power.

Charles Kaiser, with two co-conspirators, staged a robbery on a road outside of Norristown, Pennsylvania in 1896, to cover up the murder of his wife Emma. The police quickly saw through the plot and Kaiser was convicted of first-degree murder.

Soon after, the police arrested his accomplices, James Clemmer and Lizzie DeKalb. DeKalb put all the blame on Clemmer, saying she had no knowledge of the conspiracy but was under Clemmer’s hypnotic spell and did whatever he said. Kaiser also changed his story, saying he too was under Clemmer’s hypnotic power. Their stories had little effect on the outcome.

Saturday, August 27, 2022

Did Lizzie Confess?

|

| Providence Evening Bulletin, Feb. 15, 1897 |

Although the arrest was real, the confession story was quickly exposed as a hoax. But not before Snow published it as fact in his 1959 book, Piracy, Mutiny and Murder.

Saturday, August 20, 2022

Ogden and Howard.

Washington Howard lived happily with his wife and two children in Charles County, Maryland until the start of the Civil War when he left to join the Confederate Army. After two years of service and several bloody battles, Howard had a change of heart. He resolved to desert the Confederates and join the Union cause. He crossed the Union lines and surrendered to the army who sent him to the Capital Prison in Washington.

There Howard met Zadoc Damrell, another Confederate deserter. After both men took an oath of allegiance to the United States the prison released them. The authorities told them that they must not be found south of the Susquehanna River, so the two men drifted north. In 1864, they found work in Gloucester County, New Jersey, and boarded at the home of Charles Ogden. That is when the trouble began for Washington Howard.

Saturday, August 13, 2022

The French Monster.

In 1874, Joseph LaPage, a French-Canadian woodcutter, raped and murdered Marietta Ball, a young schoolteacher in St. Albans, Vermont. He was released for lack of evidence. A year later he struck again, raping and brutally murdering 17-year-old Josie Langmaid in Pembroke, New Hampshire. After two contentious trials, he was convicted of Josie Langmaid’s murder.

Read the full story here: Josie Langmaid-"The Murdered Maiden Student."

Saturday, August 6, 2022

Mrs. Southern's Sad Case.

That autumn, Southern proposed to Kate Hambrick, and the two were married. They lived happily for several months until Bob began staying out late without explanations. Kate began hearing rumors that Bob was still meeting with Narcissa. They had been seen walking together in the woods several times since the wedding. The news made Kate intensely jealous.

Saturday, July 30, 2022

Phrenological Character of Reuben Dunbar.

Saturday, July 23, 2022

"Bad Tom" Smith.

When the police arrived, Catherine McQuinn confessed to the murder. She said they had all been drinking, and when Tom Smith was lying in a drunken stupor, Rader had assaulted her, and she shot him in self-defense. This explanation was not out of line with her reputation. She was a rough, coarse woman with black hair and a face and voice more masculine than feminine. Though she was sometimes referred to as “Widow McQuinn,” her husband was alive but had been committed to the Eastern Kentucky Lunatic Asylum. Catherine had an adulterous relationship with a store clerk from town, and when her husband heard of the affair, he became a raving maniac.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

The Mysterious Murder of Bessie Little.

Saturday, July 9, 2022

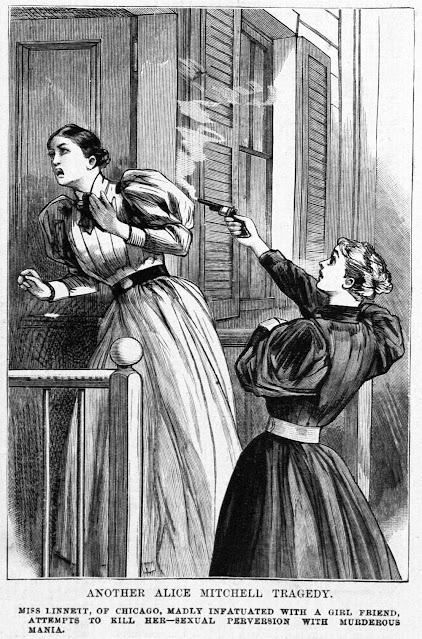

Mad Infatuation.

Mary went to the back door and asked Frances to come outside and talk. Frances refused, and as she turned to leave, Mary drew a revolver and fired four shots. Three of them missed, but one struck the back of her head, wounding her scalp. Frances hurried upstairs while her sister sent for a physician. A neighbor who heard the shots summoned the police.

Saturday, July 2, 2022

Strang Shooting Whipple.

1n 1827, Elsie Lansing lived with her husband John, in Cherry Hill,

the stately mansion overlooking the Hudson River near Albany, New York. Jesse

Strang was a servant living in the basement. When Elsie and Jesse fell in love,

their torrid affair led to the murder of John Whipple.

Read the full story here: Albany Gothic.

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Murder by Mail.

|

| Mrs. Cordelia Botkin |

Ida Deane died on Thursday. By Friday, four other members of the party were dead, including Mary Dunning. The cause appeared to be some form of food poisoning, but only those who ate the candy were stricken, the rest experienced no illness. A chemist analyzed the chocolates and found that they contained a large amount of arsenic, with some grains as large as coffee grounds.

Saturday, June 18, 2022

The Meierhoffer Murder.

Read the full story here: Who Shot Meierhoffer?

Saturday, June 11, 2022

Murdered in Church.

Ferdinand Hoffman, a German immigrant, arrived in Canton, Ohio, in 1864. There he met Caroline Yost, and after a brief courtship, he proposed to her. Caroline’s parents opposed the marriage because they did not trust Hoffman and knew nothing of his background. Predictably, their opposition only drove Caroline closer to Ferdinand, and the couple eloped.

The Yosts' suspicions of Hoffman’s character proved justified. Before coming to Canton, Hoffman was an “unprincipled vagabond” who engaged in counterfeiting and horse stealing. Caroline learned firsthand of his bad character when he began to abuse her and engage in criminal activities. He was caught stealing from her father and sentenced to prison, but he was released early when he agreed to join an Ohio regiment fighting for the Union. He soon deserted and returned home with a head wound that he claimed resulted from a rebel guerilla gunshot. It was later revealed that he received the wound in a Cincinnati gambling hell.

Friday, June 10, 2022

Free!

For a limited time...

Download a free sample chapter of

So Far from Home: The Pearl Bryan Murder

Purchase So Far from Home on Amazon.

Saturday, June 4, 2022

Tragedy on 30th Street.

Saturday, May 28, 2022

The Neosho Murder.

Saturday, May 21, 2022

Mashing Murderer Maxwell.

Saturday, May 14, 2022

Shot by His Sister-in-Law.

Jane Sullivan was arrested for murder and held on $5,000 bail. At the inquest, she told her side of the story. On three different occasions, Patrick “attempted to take undue liberties of the most insulting character.” The night before the murder Patrick entered the bedroom and attempted outrage, but Jane fought him off. The next morning, he tried again, and she defended herself with a butcher knife. He said if she told James he would kill her.

The Daily Inter Ocean said, “She bore her burning mortification and indignation in silence until it could no longer be endured and then sought relief in the fatal avenging act.”

The Illustrated Police News had a different point of view: “The women of the interior of California possess an Amazonian spirit, which is partly owing to the wilderness of their surrounding and partly to the lack of proper training. We sincerely hope Mrs. Sullivan may suffer the full penalty of her crime without regard to her sex.”

Sources:

“A California Tragedy,” Daily Inter Ocean, November 20, 1871.

“A Man Shot by his Sister-in-Law at Bay Point California,” Illustrated Police News, November 16, 1871.

“Murder,” Evening Termini, November 2, 1871.

“Pacific Coast Items,” Sacramento Daily Union, October 30, 1871.

“Pacific Coast,” Commercial Advertiser, October 31, 1871.

.jpg)