The victims were Xavier and Aglae Wilhelm (no relation), who were married in France sixteen years earlier. She was 16 and he was 25. The age difference was a problem from the beginning; Aglae liked to flirt, and Xavier was profoundly jealous.

They emigrated to America and ended up in St. Louis. Aglae had some money, and they used it to open a coffee restaurant and ice cream parlor. They were raising two children, but business was bad, and Xavier and Aglae were constantly quarreling. Aglae couldn’t take it anymore, and in 1880, she took the children back to France.

Xavier followed soon after and persuaded her to return to St. Louis. They left the children in France and came back to the city with a new business plan. They purchased the two-story building on Poplar Street, opened a saloon on the first floor, and a brothel on the second floor.

Sometime later, Xavier returned to Paris to recruit new blood for their house of ill-fame. He secured three young girls by telling them they would work as domestics in a fine hotel, for fabulous wages. The authorities in France got wind of his scheme and managed to rescue two of the girls. He returned to St. Louis with one.

During his absence, Xavier put his bartender, Jean Morrel, in charge of the saloon. Upon his return, Xavier began to suspect that Morrel had taken charge of his wife as well. The old jealousies returned, and he swore out a warrant charging his wife and her paramour with adultery. On February 5, the case came before a judge who dismissed it for want of evidence. Racked with jealousy and devoid of hope, Xavier put an end to their problems with four gunshots.

The coroner’s inquest returned the only possible conclusion:

Verdict: Aglae Wilhelm came to her death from the effects of bullets fired from a revolver at the hand of her husband, Xavier Wilhelm, deceased at 109 Poplar Street.

Verdict: Xavier Wilhelm, suicide by gunshot wound.

Morbid fascination with the crime was so strong in St. Louis that people visited the scene of the crime all day to gaze upon the place where blood had been shed. Crowds gathered at the morgue, though the bodies were covered and kept behind closed doors.

Public fascination with the crime was matched by utter disdain in the press for both Xavier and Aglae. The Memphis Daily Appeal called it A “fitting end to a bad pair.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch said:

Mr. Wilhelm is to be congratulated upon his success. As a rule, the blackguards who murder women are so exhausted by the manly exercise that they miserably fail when they attempt to do a good turn in the same line for themselves.

Sources:

“The Bloody End,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, February 6, 1881.

“Fitting End of a Bad Pair,” Memphis Daily Appeal, February 6, 1881.

“Lust and Lead,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 6, 1881.

“News Article,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 5, 1881.

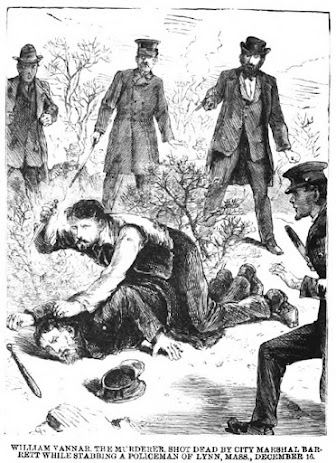

“The Wilhelm Horror in St. Louis,” Illustrated Police News, February 26, 1881.

.jpg)