Benjamin and Mary Merrill lived with their four-year-old son on Illinois Street in Chicago, where they ran a boarding house. During

the day, Benjamin worked as a broker, and Mary took care of the house along

with their chambermaid, Hattie Berk.

In May 1888, 22-year-old Andrew J. Martin took residence in

the Merrills’ boarding house. He worked nights as a stationary engineer for the

Union Steamboat Company. During the day, he lounged around the house, trying to

ingratiate himself with Mrs. Merrill. 33-year-old Mary Merril, a tall,

attractive brunette, was pleasant toward Martin, but was happily married and had no

interest in his advances.

By December 1888, Martin was desperately in love and would

not leave Mary alone. When other boarders began commenting on Martin’s behavior,

Hattie Berk took their concerns to Mary.

Martin learned of this and on December 10, he approached Mary,

who was sitting in the parlor, and tried to persuade her to discharge Hattie.

He told her that Hattie was a loose character and would bring disgrace upon the

house. Mary turned on him and said it was time for him to attend to his own

business and leave the affairs of the house alone. She did not care to have any more of his

interference in her business and hoped he would leave the house as soon as he

could find another place to live.

“Do you mean that?” Martin asked.

“I certainly do, Mr. Martin,” said Mary, “It will be best

all around if you do.”

Martin said no more; he got up and left the house. Mary went

upstairs to the room where Hattie was making the bed.

“Hattie, don’t you think I have a right to mind my own

business?” said Mary, perhaps feeling guilty about being so harsh with Martin.

“Why certainly,” said Hattie, and they discussed Martin’s

disruptive behavior.

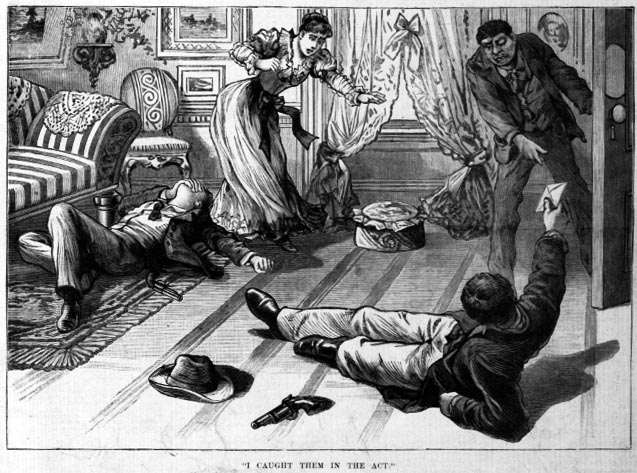

Martin came back into the house and quietly climbed the

stairs. He stood for a moment outside the room and overheard their

conversation. Then he entered the room, and “affecting a devilish suavity,” he

drew a pistol from his pocket.

|

Hattie fled downstairs, picked up the Merrills’ son, and ran

into the street screaming. She drew the attention of a policeman, who followed

her back to the house. The upstairs room was a revolting sight. Martin lay

dead, face up on the floor. Mary, lying in a pool of blood, was still alive. Conscious,

but unable to speak, she lay that way for three hours before dying.

When Benjamin Merrill heard the news of his wife’s murder,

he became hysterical and rushed home from work. Though he knew the killer was

dead as well, he screamed, “Let me at him. He should be drawn and quartered.”

Later, he spoke more calmly:

No husband ever loved a wife more than I did mine. She was so sympathetic, and glorified in my success, and sympathized in my failures. She was all that a wife could be, true as steel and pure as a virgin.

Martin was a boy, a country lad. He was a good-hearted fellow, too, and often took our little boy to plays. Of course, he loved my wife. Who could blame him for loving her? But I was not jealous, for she told me everything and only looked on him as I did, as a good-natured country boy.

Benjamin was not well enough to testify at the coroner’s

inquest the following day. Hattie Berk, the

eyewitness, told the whole story on

the stand. The jury came to the only conclusion possible: that Andrew Martin

committed suicide after shooting Mary Merrill twice.

Sources:

“Double Tragedy in Chicago,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 11, 1888.

“Faithful to the Last,” Evening Post, December 11, 1888.

“For Love of His Landlady,” News and Courier, December 11, 1888.

“The Martin Merrill Tragedy,” Chicago Daily News, December 11, 1888.

“Martin's Awful Crime,” Chicago Daily News, December 11, 1888.

“The Merrill Martin Murder,” Daily Inter Ocean, December 12, 1888.

“Sensational Double Tragedy,” Indianapolis Journal., December 11, 1888.

.jpg)