|

|

Saturday, March 18, 2023

Francis Colvin's Skull.

Saturday, April 23, 2022

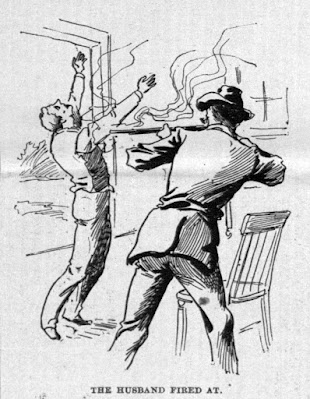

Shot Man and Wife.

On November 18, 1891, their neighbor, William Keck, aged 50, stopped by for a visit. He was carrying a double-barreled shotgun and said he had been out shooting. They invited him to stay for dinner, and Keck accepted. After dinner, William was sitting by the window watching the chickens when, without provocation, Keck grabbed his shotgun and emptied one barrel into William’s back. Jeannette ran from the house screaming, and Keck dragged her back into the cabin, threw her on the floor, and fired the second barrel into her head.

She died immediately, but William was still alive. Keck went to the woodpile, seized an axe, and struck William on the side of the head. Though badly wounded, William was able to wrestle the axe away from him. Keck grabbed a piece of firewood and beat William unconscious.

A few days earlier, Keck had borrowed twenty-five cents from William Nibsh and saw that there was more money in a bedroom drawer. After knocking William unconscious, Keck went to the drawer and took all the money—six dollars, mostly in silver. Relations between Keck and the Nibsh family had always been friendly; robbery appeared to be the only motive for the murder.

Keck left the cabin and stopped to buy some coal before going home. He paid with silver coins, believed to be from the stolen money.When William regained consciousness, he began crawling to the house of his neighbor, Mr. Druckenmiller, about a hundred yards away. He arrived at the door about two hours after the murder. Druckenmiller spread the word, and a party of men went back to the Nipsh cabin. They found that Keck had returned, possibly to look for more money. The men grabbed him and held him under guard until policemen from the city could arrive.

Before the police arrived, a vigilance committee of at least a hundred men amassed at the cabin and took Keck outside, intending to hang him from the nearest tree. Mrs. Joseph Masonheimer, daughter of the victims, intervened and persuaded the men not to wreak their vengeance on the murderer but to let the law punish him. The police came and took him to jail in Allentown.

William Keck had a bad reputation in Lehigh County and had served several terms in jail. Most recently, he was sentenced to six months in Easton Jail for threatening to kill his wife and daughter. He claimed he was innocent of the Nibsh assault and murder, but when brought to jail, he begged the police to shoot him and end his miserable life.

Under heavy guard, Keck was taken back to Ironton for the coroner’s inquest. William Nibsh, still in serious condition, was sworn in to testify. With great deliberation, he kissed the Bible, then, pointing to Keck, said, “This is the man who shot me, struck and hit me with a club and axe and shot and killed my wife.” Nibsh died shortly after testifying. Keck was charged with two counts of first-degree murder.When Keck’s trial began the following January, the vigilance committee had grown to 200 men, and they occupied seats in the courtroom. They made it known that should the verdict be acquittal, they would mob both Keck and the jury. Keck was still pleading not guilty and now claimed that William Nibsh shot his wife and attempted to shoot Keck. Keck then killed Mibsh in self-defense. When the jury came back, the vigilantes did not have to mob anyone—the verdict was guilty of first-degree murder.

After an appeal and a temporary reprieve to go before the board of pardons—both of which failed—William Keck was sentenced to hang on November 11, 1892. On November 10, Keck cheated the gallows; the guard found him lying dead in his cell. There were no marks of violence and no traces of poison, so the coroner’s jury found that Keck had died of “nervous prostration superinduced by the fear and terror of execution imminent.”

A week later, after a toxicological examination of Keck’s body, the jury had to revise their verdict. Keck had died from ingesting arsenic, probably smuggled in by one of the relatives or friends who visited the jail before the scheduled hanging. They now called the cause of death “arsenical poison, self-administered with suicidal intent.” The jury blamed laxity of prison discipline and called for prompt action and reform.

Sources:

“An Aged Woman Murdered,” Watertown Daily Times, November 19, 1891.

“Daughter's Act,” Evening Herald, November 20, 1891.

“Died of Arsenic, Not Fright,” Pittsburg Dispatch, November 20, 1892.

“Jury and Prisoner to be Mobbed,” Freeland Tribune, January 7, 1892.

“Keck Cheated the Gallows,” Evening Herald, November 11, 1892.

“Keck Murder Trial,” Patriot, January 11, 1892.

“Keck's Poisonous Dose,” Freeland Tribune, November 28, 1892.

“Murderer Keck Convicted,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 1892.

“Murderer Keck in Great Glee,” Patriot, September 2, 1892.

“A Murderer Narrowly Esca[es Lynch,” Patriot, November 20, 1891.

“Nibch Dies from Wound,” Patriot, November 30, 1891.

“The Nipsh Murder,” Patriot, November 23, 1891.

“Shot Man and Wife,” National Police Gazette, December 12, 1891.

“Wife Dead, Husband Dying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1891.

Saturday, April 2, 2022

Who Killed Lottie Morgan?

Hurley, Wisconsin, a tough iron mining town, was the

scene of many brutal crimes, but none more startling than the 1890 murder of

Lottie Morgan. She was an actress who performed in variety theaters in Hurley and the

surrounding area. Though she lived with Johnny Sullivan, a Hurley politician, she was known to have many lovers who kept her supplied with money and jewelry. Her arrangement with Sullivan may have been more about business than

romance.

Lottie Morgan was well-known, well-liked, and

reportedly one of the prettiest women on the range. Lottie was a prostitute,

but newspapers used euphemisms to soften her notoriety—she was a courtesan, a

sporting woman, one of the demimondes, of more than doubtful reputation. The

Montreal River Mine and Iron County Republican said, “She carried herself

with all the propriety possible for her class, was vivacious, sprightly, well

informed, and was universally known here and at Ironwood and Bessemer.”

On the morning of April 12, 1890, the mutilated body

of Lottie Morgan was found in the filthy alley between two low dives on

Hurley’s main drag. She lay in a pool of coagulated blood with a deep gash in

the side of her head, about 4 inches long, from the temple back. At her feet

was her own 32 caliber revolver. A reporter found a bloodstained axe in a

nearby shed, believed to be the murder weapon.

None could find a motive for the murder. Lottie was

fully clothed when found and had not been molested. The police ruled out

robbery because Lottie was still wearing her diamond earrings and other

jewelry, valued at more than $5,000.

One of Lottie’s lovers was an ex-policeman, and some

speculated that she was working as a police spy. The criminals

who discovered her secret took their revenge.

The police and public favored another, more specific, theory. A

recent nighttime robbery at the Hurley Iron Exchange Bank netted the thieves $39,000.

Lottie had been subpoenaed to testify at the trial because the bank’s interior

could be seen from the window of Lottie’s apartment. The court found Ed Baker

and Phelps Perrin guilty of the robbery even without Lottie’s testimony, but

they became the prime suspects in her murder.

Lottie Morgan’s elaborate funeral included a beautiful

display of flowers and a procession featuring a brass band. The town raised

nearly $200 to investigate the crime. A grand jury was convened to uncover the

mysterious plot that led to Lottie’s murder.

But nothing was uncovered. In May, the County Board of

Supervisors offered a $500 reward for the apprehension of the murders, but

nothing came of this either. As time went on, the police and people of Hurley faced newer crimes and Lottie's case went cold. Lottie Morgan’s name disappeared from the newspapers and her unsolved murder was eventually forgotten.

Sources:

“Brained with an Ax,” St Paul daily globe, April 12, 1890.

“Brevities by Wire,” Aberdeen Daily News, April 12, 1890.

“Domestic,” Daily Inter Ocean, April 12, 1890.

“Found Murdered,” Erie Morning Dispatch, April 12, 1890.

“The Hurley Murder,” Bay City Times, April 12, 1890.

“A Hurley Murder,” Duluth News-Tribune, April 12, 1890.

“Lottie Morgan Murdered,” Montreal River Miner and Iron County Republican, April 10, 1890.

“Lottie Morgan's Murder,” Portage Daily Democrat, April 14, 1892.

“Murdering a Woman,” Milwaukee Journal, April 11, 1890.

“News of Wisconsin,” Boscobel Dial, May 26, 1892.

“To Cover a Crime,” Argus-Leader, May 17, 1890.

“Was She an Important Witness?,” Milwaukee Journal, May 14, 1890.

“Who Killed Lottie Morgan?,” Illustrated Police News, April 26, 1890.

“Who Killed Lottie Morgan?,” Detroit Free Press, April 12, 1890.

“Why Lottie was Murdered,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 14, 1890.

Saturday, February 19, 2022

The Long Island Tragedy.

Saturday, September 11, 2021

Shot by Her Stepson.

“Shortly after 5 o’clock, I came from the kitchen and was putting oil in my lamp when my stepson, Thomas McCabe, fired a shot at me. I fell on my hands and knees and he said, ‘I done it! I done it!’ I said, ‘Why, Tom; why did you do it?’ He said nothing In reply, but stooped over me and took the contents of my pocket. I said, ‘it’s the money of the Land League,’ of which my husband is an officer. He also took my watch and an opera chain. I than said, ‘Oh, Tom; oh, Tom, don’t take my watch and chain!' He said, ‘I will take It; I want money to leave the city.’ I said, ‘Oh, Tom, don’t leave me, I never will mention your name. I will say I fell if you will only lift me up.’ He said, ‘I am not able,’ Then he left me. I called for help. I was paralyzed and could not get up, but after a long while Mrs. Whaley came In, and my stepson threw the pistol into his uncle’s bed. I saw him do it. When he went out be locked the door. I knew of no reason except that be wanted to rob me, I never had an angry word with him of late.”

Thomas McCabe bought a new suit of clothes with the money he stole from his stepmother, then went to a shooting gallery in the Bowery. He was practicing pistol shooting when the police arrested him.

McCabe had come with his father and stepmother from Ireland about four years earlier. He enjoyed life in New York, “but his tastes did not run in orderly grooves.” He did not like the discipline of school, was often truant, and caused trouble for his teachers and parents. His father would have whipped him many times, but for his stepmother’s intervention—she was thought to be too forbearing with him.

He finally got a job as a messenger for the District Telegraph Company but was often absent from this as well. McCabe was fired from the job but was afraid to tell his parents. Instead, he decided to rob them and leave town. When arrested for shooting his mother, McCabe showed no remorse.

At his trial the following September, Thomas McCabe was represented by William Howe of the firm Howe and Hummel, the most successful criminal lawyers in New York. McCabe’s plea was insanity. Under Howe’s cross-examination, McCabe’s father said Thomas had been weak-minded since birth, and at the James Street School, a Christian Brother had sent him home because he could make no progress with his studies and because he had “head trouble.” He was a boy of very weak intellect and was afflicted with epileptic fits.

Howe was not able to win an acquittal but was able to reduce the charge to second-degree manslaughter. Recorder Smyth, who presided over the case, was unhappy with the verdict and said this to McCabe as he handed down the maximum sentence:

“McCabe, the jury in your case took a more lenient and merciful view of your crime than your cowardly action deserved. They might well have rendered a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree on the evidence, and you would have been at the bar of this Court answering with your life for the life you have taken. You were most ably defended, and you have already had all the protection and mercy that ought be bestowed on you. The sentence of the Court is that you be confined in State Prison for seven years.”

Sources:

“A Boy Matricide,” New York Herald, September 20, 1882.

“The Boy Murderer Sentenced,” Evening Star, September 29, 1882.

“City News Items,” New York Herald, July 12, 1882.

“Duties Neglected For A Convention,” New York Tribune, September 21, 1882.

“A Fatal Shot,” Evening Bulletin, May 16, 1882.

“Gotham Gossip,” Times-Picayune, May 19, 1882.

“The M'Cabe Trial,” Truth, September 26, 1882.

“Morning Summary,” Daily Gazette, May 15, 1882.

“Seven Years for a Life,” New York Herald, September 30, 1882.

“Shot by Her Stepson,” Cambria Freeman, May 19, 1882.

“Thomas McCabe,” National Police Gazette, June 10, 1882.

“The Trial of Thomas M' Cabe,” New York Herald, September 26, 1882.

Saturday, February 13, 2021

Saturday, September 12, 2020

Horrible Murder in Twelfth Street.

Mrs. Sarah Shancks owned a high-end millenary concern—“a fancy thread and needle store”—at 22 East 12th Street. At around 10:00 AM, the morning of December 7, 1860, Susan Ferguson, who worked as a seamstress for Mrs. Shanks, entered the store but could not find her employer. She went to the back room where Mrs. Shanks resided and found her lying on the floor in a pool of blood. Her throat had been slashed, and she was surrounded by broken glass and crockery. Susan ran out of the store to alert the police.

Saturday, August 15, 2020

Saturday, May 30, 2020

Miss Elizabeth Petty.

Saturday, September 7, 2019

“A Romance of Crime.”

His personal life was just as erratic. At age 23 he married Mary Jane Andres and left her after two years. Without the formality of a divorce, he married Mary Gahan soon after. She already had an illegitimate son who took his father’s name, Alphonse F. Cutaiar. Logue mistreated Mary, so she left him, went home to her father and died in 1869. Before Mary Gahan left him, Logue had taken up with her sister Johanna. Jimmy Logue and Johanna Gahan were married in the dock of the Central Police Station in 1871 as Logue was preparing to serve a seven-year sentence at Cherry Hill Prison for burglary.

Saturday, June 1, 2019

The Delaware Avenue Murder.

Saturday, March 16, 2019

Lewis Wolf Webster.

After hearing the man speak, Mrs. Harrington said, “I think I know you.”

“You do, do you?” he responded and fired the pistol hitting her in the left arm. As he did so, the handkerchief fell from his face and she saw to was Lewis Webster, the man she suspected. Mrs. Harrington ran to the kitchen, and he fired again hitting the same arm. She rushed out to the street and with blood streaming from her wounds ran to a schoolhouse some 40 yards away from where an entertainment was in progress.

Saturday, October 20, 2018

A Most Horrible Affair.

Saturday, October 6, 2018

The Mysterious Murder of William Wilson.

Major William C. Wilson was a dealer in old manuscripts and proprietor of Wilson’s Circulating Library on Walnut Street in Philadelphia. He had fought in the Civil war with the 104th New York Infantry and received two field promotions for bravery, first to captain then to major. After the war, he settled in Philadelphia where he led a solitary and somewhat eccentric life. He had few acquaintances outside the Franklin Chess Club which he visited each evening between 7:00 and 10:00—the Philadelphia Inquirer would later call him “one of the most lonely characters in the city.”

Major William C. Wilson was a dealer in old manuscripts and proprietor of Wilson’s Circulating Library on Walnut Street in Philadelphia. He had fought in the Civil war with the 104th New York Infantry and received two field promotions for bravery, first to captain then to major. After the war, he settled in Philadelphia where he led a solitary and somewhat eccentric life. He had few acquaintances outside the Franklin Chess Club which he visited each evening between 7:00 and 10:00—the Philadelphia Inquirer would later call him “one of the most lonely characters in the city.”Saturday, February 3, 2018

A Peculiar Affair.

Mrs. Bennett grabbed a revolver and shot him twice. Bleeding profusely, the man snatched the pistol from her then left the same way he came in. Fearing another attack, Mrs. Bennett and her daughter barred all the doors and windows and stayed up until morning. The intruder had been another of their neighbors, Leonard Wilkinson; Mrs. Bennett had recognized him right away.

Saturday, January 6, 2018

The Squibb Family Murder.

Saturday, July 9, 2016

A Tale of Deepest Crime.

Saturday, March 21, 2015

The Nicely Brothers.

.jpg)