Melinda Jones (nee Luce) married Samuel Jones, a farmer, around 1859. The two had grown up together in Washington, Maine, and they had a happy marriage raising three children. But Samuel grew tired of farming and decided to go west and seek his fortune. In California, he had no luck prospecting and ended up working as a farmhand. At first, he would send Melinda small sums of money, but soon his letters stopped completely. Melinda made some inquiries and concluded that Samuel was dead. Not long after, she married William Vannar, another of her childhood friends.

As the relatives predicted, the marriage was a stormy one. There were periods of calm when the couple seemed happy, but Vannar could not stay sober, and when drunk, he would beat and abuse his wife. Four times she left Vannar and went home to her parents, but Melinda remained infatuated with Vannar, and each time she went back to him.

In June 1871, Melinda had gone back to her parent’s home, and Vannar went to get her back. When she refused to go with him, he stabbed her in the breast. Her mother tried to intercede, and Vannar stabbed her as well. The wounds were not serious; Vannar was arrested for assault. He was released on $400 bond and fled the town.

While on the run, Vannar would write and tell Melinda where he was. Four months after the incident, Vannar returned, and Melinda took him back as if nothing had happened. This time she abandoned her children and traveled with him to Lynn, Massachusetts, where Vannar’s sister lived.

Their time in Lynn followed the familiar pattern—periods of marital bliss punctuated by drunken abuse. The night of December 16, 1871, the couple attended a ball at Wyoma Square in Lynn. Allegedly, Vannar took jealous offense at the attention paid to Melinda by another man. The matter appeared to be forgotten the next morning. Vannar arose at 5:00, built a fire, and went out to buy some liquor. When he returned, they sat down to breakfast and were observed laughing and joking together about the previous night.

After breakfast, Vannar began drinking. His shirt had gotten dirty the night before, and Melinda said she would take it downstairs and wash it. He said he would hire someone to do it and save her the trouble. She took it downstairs anyway. Her disregard of his wishes infuriated Vannar, and he went down after her. A few minutes later, boarders in the house heard bloodcurdling screams coming from the basement. Mrs. Rodney, one of the boarders, saw Vannar come up the stair holding a knife, his clothing saturated with blood. He casually walked to the sink, washed his hands, cleaned his knife, and put it in his pocket.

“Give my coat and gloves to my sister,” he said to Mrs. Rodney, “for she (meaning his wife) is dead now, and I have got to die.”He went back downstairs, stepped over the corpse, and left through the back door.

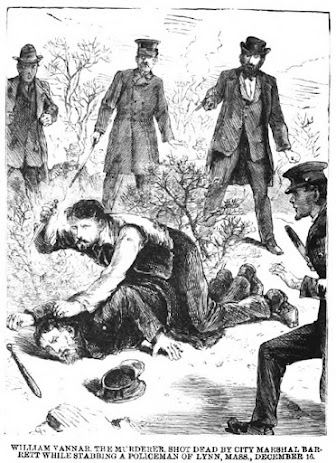

News of the murder traveled fast, and men turned out by hundreds to pursue Vannar. They had him cornered against a rock in the woods, but Vannar had his knife poised, ready to thrust, and no one would approach him. Officer John Thurston attempted to rush him with a club, but he slipped and fell. Vannar was on him instantly, dealing heavy blows with his knife. City Marshal, Daniel N. Barrett, drew his revolver and fired five shots, killing Vannar.

Officer Thurston suffered several stab wounds to the face and head and a bullet through his hand, but he survived the ordeal. A coroner’s inquest on December 21 ruled that Marshal Barrett’s action was justified.

Sources:

“The Lynn Tragedy,” National Aegis, December 23, 1871.

“News Article,” Gloucester Telegraph, December 20, 1871.

“News Article,” Evening Bulletin, December 26, 1871.

“The Recent Murder at Lynn Massachusetts,” Wheeling daily register, December 23, 1871.

“Tragedy in Lynn,” Republican journal, December 21, 1871.

.jpg)

0 comments :

Post a Comment