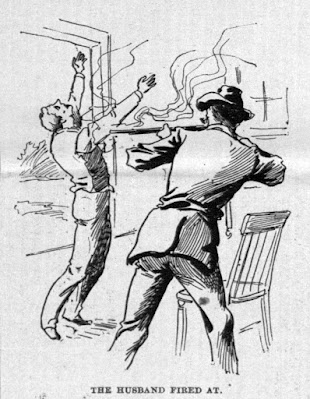

On November 18, 1891, their neighbor, William Keck, aged 50, stopped by for a visit. He was carrying a double-barreled shotgun and said he had been out shooting. They invited him to stay for dinner, and Keck accepted. After dinner, William was sitting by the window watching the chickens when, without provocation, Keck grabbed his shotgun and emptied one barrel into William’s back. Jeannette ran from the house screaming, and Keck dragged her back into the cabin, threw her on the floor, and fired the second barrel into her head.

She died immediately, but William was still alive. Keck went to the woodpile, seized an axe, and struck William on the side of the head. Though badly wounded, William was able to wrestle the axe away from him. Keck grabbed a piece of firewood and beat William unconscious.

A few days earlier, Keck had borrowed twenty-five cents from William Nibsh and saw that there was more money in a bedroom drawer. After knocking William unconscious, Keck went to the drawer and took all the money—six dollars, mostly in silver. Relations between Keck and the Nibsh family had always been friendly; robbery appeared to be the only motive for the murder.

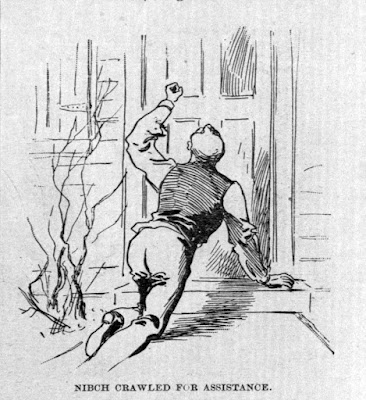

Keck left the cabin and stopped to buy some coal before going home. He paid with silver coins, believed to be from the stolen money.When William regained consciousness, he began crawling to the house of his neighbor, Mr. Druckenmiller, about a hundred yards away. He arrived at the door about two hours after the murder. Druckenmiller spread the word, and a party of men went back to the Nipsh cabin. They found that Keck had returned, possibly to look for more money. The men grabbed him and held him under guard until policemen from the city could arrive.

Before the police arrived, a vigilance committee of at least a hundred men amassed at the cabin and took Keck outside, intending to hang him from the nearest tree. Mrs. Joseph Masonheimer, daughter of the victims, intervened and persuaded the men not to wreak their vengeance on the murderer but to let the law punish him. The police came and took him to jail in Allentown.

William Keck had a bad reputation in Lehigh County and had served several terms in jail. Most recently, he was sentenced to six months in Easton Jail for threatening to kill his wife and daughter. He claimed he was innocent of the Nibsh assault and murder, but when brought to jail, he begged the police to shoot him and end his miserable life.

Under heavy guard, Keck was taken back to Ironton for the coroner’s inquest. William Nibsh, still in serious condition, was sworn in to testify. With great deliberation, he kissed the Bible, then, pointing to Keck, said, “This is the man who shot me, struck and hit me with a club and axe and shot and killed my wife.” Nibsh died shortly after testifying. Keck was charged with two counts of first-degree murder.When Keck’s trial began the following January, the vigilance committee had grown to 200 men, and they occupied seats in the courtroom. They made it known that should the verdict be acquittal, they would mob both Keck and the jury. Keck was still pleading not guilty and now claimed that William Nibsh shot his wife and attempted to shoot Keck. Keck then killed Mibsh in self-defense. When the jury came back, the vigilantes did not have to mob anyone—the verdict was guilty of first-degree murder.

After an appeal and a temporary reprieve to go before the board of pardons—both of which failed—William Keck was sentenced to hang on November 11, 1892. On November 10, Keck cheated the gallows; the guard found him lying dead in his cell. There were no marks of violence and no traces of poison, so the coroner’s jury found that Keck had died of “nervous prostration superinduced by the fear and terror of execution imminent.”

A week later, after a toxicological examination of Keck’s body, the jury had to revise their verdict. Keck had died from ingesting arsenic, probably smuggled in by one of the relatives or friends who visited the jail before the scheduled hanging. They now called the cause of death “arsenical poison, self-administered with suicidal intent.” The jury blamed laxity of prison discipline and called for prompt action and reform.

Sources:

“An Aged Woman Murdered,” Watertown Daily Times, November 19, 1891.

“Daughter's Act,” Evening Herald, November 20, 1891.

“Died of Arsenic, Not Fright,” Pittsburg Dispatch, November 20, 1892.

“Jury and Prisoner to be Mobbed,” Freeland Tribune, January 7, 1892.

“Keck Cheated the Gallows,” Evening Herald, November 11, 1892.

“Keck Murder Trial,” Patriot, January 11, 1892.

“Keck's Poisonous Dose,” Freeland Tribune, November 28, 1892.

“Murderer Keck Convicted,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 1892.

“Murderer Keck in Great Glee,” Patriot, September 2, 1892.

“A Murderer Narrowly Esca[es Lynch,” Patriot, November 20, 1891.

“Nibch Dies from Wound,” Patriot, November 30, 1891.

“The Nipsh Murder,” Patriot, November 23, 1891.

“Shot Man and Wife,” National Police Gazette, December 12, 1891.

“Wife Dead, Husband Dying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1891.

.jpg)

0 comments :

Post a Comment