Mrs. J.W. Gibbons was away from her home in Ashland, Kentucky, on December 23, 1881. She left behind her 18-year-old son Robert, her 14-year-old daughter Fannie, and 17-year-old Emma Thomas (aka Carico), who was staying with them. Mrs. Gibbons returned the following day to find her home burned to the ground and all three inhabitants dead.

Neighbors

discovered the fire around 5:00 am on December 24, and two of them were able to

drag the bodies out of the file. Fanny’s skull was crushed by a blunt

instrument, and Emma had been strangled. It appeared that both girls had been

raped. Robert, who had lost a leg in a railroad accident, was no match for the

intruders. He ran outside to give an alarm. Before he could do so, the killer

struck him from behind with a hatchet. The victims’ clothes were saturated with

coal oil and were partially burned. It appeared that the killer or killers had tried

to start a fire by lighting the clothing. The fire did not catch, so they

returned and set the house on fire.

The town

of Ashland was shocked at the news. The Wheeling Register called it “one of the

most atrocious and hellish murders ever committed in a civilized community.”

The town raised $1,000 as reward for the apprehension of the killer and sent

for private detective John T. Norris.

The axe

and crowbar used in the murders belonged to the Gibbons family, so the killers

must have known where these things were kept. Norris was convinced that the

killer was Mrs. Gibbons’s husband, a thriftless drinking man who had been kicked

out of the house several weeks earlier because of his dissipated habits. The community

found it hard to believe that Gibbons would rape his own 14-year-old daughter,

but the postmortem physicians could not say for sure that the girls had been

raped. Norris thought that Gibbons had mutilated the bodies after death to make

it appear they were raped to throw suspicion on someone else.

The

newspapers reported several stories attributed to Mrs. Gibbons, suggesting that

J.W. Gibbons was dangerously unstable. He was subject to spells of temporary insanity,

frequently acting like a lunatic. He had threatened to kill his family, cut their

heads off, and burn down the house. He pranced around the house brandishing a

butcher knife and at one time had proposed a suicide pact with his wife. Norris

was searching for Gibbons and believed he would soon be in custody if he had

not already killed himself.

Not everyone

believed that Gibbons was guilty. In the nearby town of Louisa, the police arrested

a black man named Willis Hockaday. He had been drinking the day of the murder

and disappeared that night. The next day he made some incriminating statements.

There was no evidence that Hockaday had any connection to the murder, and the

police released him. Hockaday barely escaped lynching.

It

turned out that the statements attributed to Mrs. Gibbons concerning her

husband’s behavior were exaggerated rumors gathered by a reporter. Mrs. Gibbons

denied making the statements. J.W. Gibbons arrived in Ashland on January 2, bringing

overwhelming proof that he was elsewhere the night of the murder. He was not

arrested.

Detective

Hefflin of the Ashland Police never believed that Gibbons was the killer; he

followed a different trail. The night of January 2, Hefflin arrested three men,

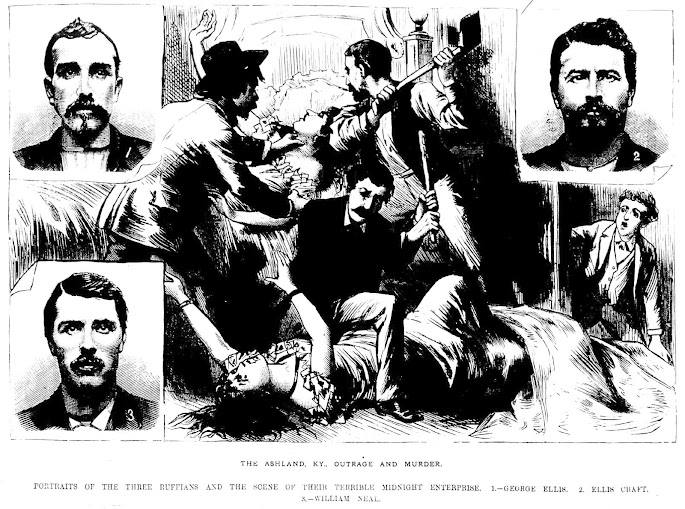

William Neal, Ellis Craft, and George Ellis.

George Ellis immediately admitted he was at the Gibbons's home the night of the murders but placed most of the blame on the other two men. He said that Neal and Craft had boasted that they would “carnally know” Miss Thomas and Miss Gibbins before Christmas. They roused Ellis late on the night of the murder and insisted he go with them to the Gibbons’s house. Reluctantly he went with them. They went in through a window, and Ellis watched as Craft raped Fannie. She cried piteously for mercy as he continued his hellish work. Neal then raped Emma Thomas as George Ellis held her arms. Afterward, Emma said, “Oh, Will, I know who you are, and I am going to tell my mother.”

The

noise aroused Robert, who went out to give an alarm when Craft hit him on the

head with an axe. Craft then told Fannie her time had come, and he struck her

on the head and killed her instantly. Neal then killed Emma Thomas.

Ellis

said the cries of the girls for mercy were terrible to listen to, and he had

not slept since. Every minute since the horrible tragedy was so vividly before

his eyes, he could not stand it any longer. He said he had prayed every day and

he was prepared to die. The other two men denied his story.

The police

took the prisoners by steamboat to Catlettsburg. They managed to secure the men

in jail there before the gathering lynch mob could get them, but everyone

believed a lynching was inevitable. The Cincinnati Commercial said, “Most

likely before this is read by the many readers of the Commercial the hell hounds

in this blood curdling drama will swing into eternity.”

Ten

armed men guarded the prisoners held at the Catlettsburg jail, and they managed

to keep them safe until their trials. William Neal confessed to the crime, but

Ellis Craft continued to plead not guilty. All three were charged with aiding, abetting,

and conspiring murder. George Ellis was separately charged with three counts of

murder, a technicality allowing him to testify against his accomplices.

Neal

changed his plea to not guilty, but all three men were convicted. Neal and Craft

were found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang. Ellis, who

testified against Neal and Craft, was found guilty of manslaughter and

sentenced to life in prison. This sentence did not sit well with the people of

Ashland. A group of about 40 masked men arrived in Catlettsburg by train, broke

into the jail through a window, unlocked Ellis’s cell, and brought him out with

a rope around his neck. They took him to a brickyard near the murder site and

hung him from a sycamore tree.

Both

Neal and Craft appealed their convictions and were granted new trials and a

change of venue to Carter County. They were taken by steamboat to Maysville, Kentucky,

guarded by 220 State troops. Five miles below Catlettsburg, a gang of men in

ferryboats opened fire on the steamboat, and the troops returned fire. The troops

killed one of the attackers and wounded several others. Five spectators on the riverbank

were killed and twenty-one wounded. The prisoners reached Maysville safely.

Neither

Neal nor Craft succeed in their second trial. Both were convicted again of

first-degree murder and sentenced to hang. In a last-ditch attempt to avoid

execution, Craft’s brother found a black man in Columbus, Ohio, who supposedly confessed

to the crime. William Direly had allegedly given a woman a bracelet that

belonged to one of the murdered girls. No one believed the story, and nothing changed. It was

thought that Craft’s friends planned to lynch Direly to draw attention from

Craft. Reportedly, the people of Ashland were extremely indignant and made sure

that Direly was treated fairly.

Ellis Craft’s

hanging on October 12, 1883 in Grayson, Kentucky, was witnessed by a large and

festive crowd. He professed innocence to the end. William Neal was hanged in

Grayson on March 27, 1885. With his dying breath, he also professed innocence.

Sources:

“The Ashland Fiends,” Memphis daily appeal., January 14, 1882.

“The Ashland Horror,” New York Herald, December 27, 1881.

“The Ashland Horror,” Indianapolis Sentinel, December 28, 1881, 1.

“Ashland Horror Three Men Arrested for Murder of the Gibbons Family,” Cincinnati Commercial, January 4, 1882.

“The Ashland Murderers,” Indianapolis Sentinel, January 12, 1882.

“The Ashland Tragedy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 14, 1882.

“The Ashland Triple Murder,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, December 31, 1881.

“Ashland's Crime,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, December 30, 1881.

“Butchered and Burned,” The Daily Interocean, December 26, 1881.

“The Criminal Record,” Knoxville daily chronicle., January 18, 1882.

“A Dead Failure,” Cleveland Leader., June 14, 1883.

“Ellis Elevated,” Cleveland Leader., June 5, 1882.

“Five Men Hanged,” New York Herald, October 13, 1883.

“George Ellis Retracts,” Indianapolis Sentinel, March 22, 1882.

“Gibbons Round,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, January 3, 1882.

“His Victims Are Avenged,” EVENING Plain Dealer, March 28, 1885.

“The Kentucky Tragedy,” BOSTON HERALD., December 27, 1881.

“The Last Scene in a Noted Tragedy,” The New York Herald, March 28, 1885.

“The Mad Mob,” Knoxville daily chronicle., January 6, 1882.

“A Matchless Horror,” National Police Gazette, January 28, 1882.

“Militia Preventing Lynching,” New-York Tribune., January 9, 1882.

“Murderers as Mourners,” The Daily Inter Ocean, January 4, 1882.

“News Article,” Daily Journal., January 20, 1882.

“News Article,” Gloucester County Democrat., March 8, 1883.

“Rape, Murder and Incendarism,” EVENING LEADER., December 27, 1881.

“Swift Kentucky Justice,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, June 5, 1882.

“Triple Murder,” Wheeling Register, December 26, 1881, 1.

“William Neil's Confession,” New York Herald, January 5, 1882.

.jpg)

1 comments :

September 12, 2022 at 9:18 AM

Yeah blame it on someone who isn't white a classic distraction method.

Post a Comment